Geometri: Perbedaan antara revisi

Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

Menambahkan bagian |

||

| Baris 1: | Baris 1: | ||

{{Periksaterjemahan|en|Geometry}} |

{{Periksaterjemahan|en|Geometry}} |

||

{{General geometry}} |

{{General geometry}} |

||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=Agustus 2020}} |

|||

{{short description|Cabang matematika}} |

|||

{{Dalam perbaikan}} |

|||

[[Berkas:Hypercube.svg|190px|thumb|[[Tersseract]] atau [[Hiperkubus]] Salah satu bentuk geometri 4 Dimensi]] |

|||

'''Geometri''' (Yunani Kuno: γεωμετρία, geo-"bumi",-metron "pengukuran"), '''ilmu ukur''', atau '''ilmu bangun''' adalah cabang [[matematika]] yang bersangkutan dengan pertanyaan [[bentuk]], [[ukuran]], [[posisi]] relatif gambar, dan [[sifat ruang]]. Seorang ahli matematika yang bekerja di bidang geometri disebut ''ahli geometri''. Geometri muncul secara independen di sejumlah budaya awal sebagai ilmu pengetahuan praktis tentang [[panjang]], [[luas]], dan [[volume]], dengan unsur-unsur dari ilmu matematika formal yang muncul di Barat sedini [[Thales]] (abad 6 SM). Pada abad ke-3 SM geometri dimasukkan ke dalam bentuk aksiomatik oleh [[Euclid]], yang dibantu oleh geometri Euclid, menjadi standar selama berabad-abad. [[Archimedes]] mengembangkan teknik cerdik untuk menghitung luas dan isi, dalam banyak cara mengantisipasi [[kalkulus integral]] yang modern. Bidang [[astronomi]], terutama memetakan posisi bintang dan planet pada falak dan menggambarkan hubungan antara gerakan benda langit, menjabat sebagai sumber penting masalah geometrik selama satu berikutnya dan setengah milenium. Kedua geometri dan astronomi dianggap di dunia klasik untuk menjadi bagian dari [[Quadrivium]] tersebut, subset dari tujuh seni liberal dianggap penting untuk warga negara bebas untuk menguasai. |

'''Geometri''' (Yunani Kuno: γεωμετρία, geo-"bumi",-metron "pengukuran"), '''ilmu ukur''', atau '''ilmu bangun''' adalah cabang [[matematika]] yang bersangkutan dengan pertanyaan [[bentuk]], [[ukuran]], [[posisi]] relatif gambar, dan [[sifat ruang]]. Seorang ahli matematika yang bekerja di bidang geometri disebut ''ahli geometri''. Geometri muncul secara independen di sejumlah budaya awal sebagai ilmu pengetahuan praktis tentang [[panjang]], [[luas]], dan [[volume]], dengan unsur-unsur dari ilmu matematika formal yang muncul di Barat sedini [[Thales]] (abad 6 SM). Pada abad ke-3 SM geometri dimasukkan ke dalam bentuk aksiomatik oleh [[Euclid]], yang dibantu oleh geometri Euclid, menjadi standar selama berabad-abad. [[Archimedes]] mengembangkan teknik cerdik untuk menghitung luas dan isi, dalam banyak cara mengantisipasi [[kalkulus integral]] yang modern. Bidang [[astronomi]], terutama memetakan posisi bintang dan planet pada falak dan menggambarkan hubungan antara gerakan benda langit, menjabat sebagai sumber penting masalah geometrik selama satu berikutnya dan setengah milenium. Kedua geometri dan astronomi dianggap di dunia klasik untuk menjadi bagian dari [[Quadrivium]] tersebut, subset dari tujuh seni liberal dianggap penting untuk warga negara bebas untuk menguasai. |

||

| Baris 9: | Baris 15: | ||

Sedangkan sifat visual geometri awalnya membuatnya lebih mudah diakses daripada bagian lain dari matematika, seperti aljabar atau teori bilangan, bahasa geometrik juga digunakan dalam konteks yang jauh dari tradisional, asal Euclidean nya (misalnya, dalam geometri fraktal dan geometri aljabar) |

Sedangkan sifat visual geometri awalnya membuatnya lebih mudah diakses daripada bagian lain dari matematika, seperti aljabar atau teori bilangan, bahasa geometrik juga digunakan dalam konteks yang jauh dari tradisional, asal Euclidean nya (misalnya, dalam geometri fraktal dan geometri aljabar) |

||

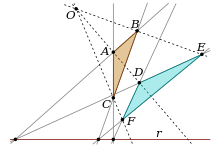

[[Berkas:Teorema de desargues.svg|thumb|right|Ilustrasi [[teorema Desargues]], hasil penting dalam [[geometri Euclidean|Euclidean]] dan [[geometri proyektif]]]] |

|||

== Sejarah == |

|||

{{Main|Sejarah geometri}} |

|||

[[Berkas:Westerner and Arab practicing geometry 15th century manuscript.jpg|right|thumb|Salah satu [[Kelompok etnis di Eropa|Eropa]] dan [[Arab]] yang berlatih geometri di abad ke-15]] |

|||

[[Berkas:Title page of Sir Henry Billingsley's first English version of Euclid's Elements, 1570 (560x900).jpg|right|thumb|[[Gambar depan]] versi bahasa Inggris pertama Sir Henry Billingsley dari Euclid ''[[Element (matematika)|Elemen]]'', 1570]] |

|||

Permulaan geometri paling awal yang tercatat dapat ditelusuri ke [[Mesopotamia]] kuno dan [[Mesir Kuno|Mesir]] pada milenium ke-2 SM.<ref>J. Friberg, "Metode dan tradisi matematika Babilonia. Plimpton 322, Pythagoras tiga kali lipat, dan persamaan parameter segitiga Babilonia", ''Historia Mathematica'', 8, 1981, pp. 277–318.</ref><ref>{{Cite book | edition = 2 | publisher = [[Dover Publications]] | last = Neugebauer | first = Otto | author-link = Otto E. Neugebauer | title = Ilmu Tepat di Zaman Kuno | origyear = 1957 | year = 1969 | isbn = 978-0-486-22332-2 | url = https://books.google.com/?id=JVhTtVA2zr8C|chapter=Chap. IV Matematika dan Astronomi Mesir|pages=71–96}}.</ref> Geometri pada awalnya adalah kumpulan prinsip yang ditemukan secara empiris mengenai panjang, sudut, luas, dan volume, yang dikembangkan untuk memenuhi beberapa kebutuhan praktis dalam [[survei]], dan [[konstruksi]]. Teks geometri paling awal yang diketahui adalah [[Matematika Mesir|Mesir]] ''[[Papirus Matematika Rhind|Papirus Rhind]]'' (2000–1800 SM) dan ''[[Papirus Matematika Moskow|Papirus Moskow]] '' (sekitar 1890 SM), [[Matematika Babilonia|Tablet tanah liat Babilonia]] seperti [[Plimpton 322]] (1900 SM). Contohnya, Papirus Moskow memberikan rumus untuk menghitung volume piramida terpotong, atau [[frustum]].<ref name="Boyer 1991 loc=Mesir p. 19">{{Harv|Boyer|1991|loc="Mesir" p. 19}}</ref> Tablet tanah liat (350-50 SM) menunjukkan bahwa astronom Babilonia menerapkan prosedur [[trapesium]] untuk menghitung posisi Jupiter dan [[Perpindahan (vektor)|gerakan]] dalam kecepatan waktu. Prosedur geometris tersebut mengantisipasi [[Kalkulator Oxford]], termasuk [[teorema kecepatan rata-rata]], pada abad ke 14.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Ossendrijver |first=Mathieu |date=29 Januari 2016 |title=Para astronom Babilonia kuno menghitung posisi Jupiter dari area di bawah grafik kecepatan waktu |journal=Ilmu |volume=351 |issue=6272 |pages=482–484 |doi=10.1126/science.aad8085 |pmid=26823423|bibcode=2016Sci...351..482O }}</ref> Di selatan Mesir, [[Nubia|Nubia kuno]] membangun sistem geometri termasuk versi awal jam matahari.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Gnomons di Meroë dan Trigonometri Awal|first=Leo|last=Depuydt|date=1 Januari 1998|journal=The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology|volume=84|pages=171–180|doi=10.2307/3822211|jstor=3822211}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archaeology.org/online/news/nubia.html|title=Neolithic Skywatchers|date=27 Mei 1998|first=Andrew|last=Slayman|website=Archaeology Magazine Archive|access-date=17 April 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110605234044/http://www.archaeology.org/online/news/nubia.html|archive-date=5 Juni 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Pada abad ke 7 SM, [[Matematika Yunani|Yunani]] ahli matematika [[Thales of Miletus]] menggunakan geometri untuk menyelesaikan masalah seperti menghitung tinggi piramida dan jarak kapal. Hal tersebut dikreditkan dengan penggunaan pertama dari penalaran deduktif yang diterapkan pada geometri, dengan menurunkan empat akibat wajar dari [[Teorema Thales]].<ref name="Boyer 1991 loc=Ionia dan Pythagoras p. 43"/> Pythagoras mendirikan [[Pythagoras|Sekolah Pythagoras]], yang dikreditkan dengan bukti pertama dari [[Teorema Pythagoras]],<ref>Eves, Howard, Pengantar Sejarah Matematika, Saunders, 1990, {{ISBN|0-03-029558-0}}.</ref> Padahal pernyataan teorema tersebut memiliki sejarah yang panjang.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Penemuan Ketidakbandingan oleh Hippasus dari Metapontum|author=Kurt Von Fritz|journal=The Annals of Mathematics|year=1945}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Pentagram dan Penemuan Bilangan Irasional|journal=The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal|author=James R. Choike|year=1980}}</ref> [[Eudoxus dari Cnidus|Eudoxus]] (408–355 SM) mengembangkan [[metode]], yang memungkinkan perhitungan luas dan volume gambar lengkung,<ref>{{Harv|Boyer|1991|loc="Zaman Plato dan Aristoteles" p. 92}}</ref> serta teori rasio yang menghindari masalah [[besaran yang tidak dapat dibandingkan]], yang memungkinkan geometer berikutnya untuk membuat kemajuan yang signifikan. Sekitar 300 SM, geometri direvolusi oleh Euclid, yang '' [[Elemen Euklides|Elemen]] '', secara luas dianggap sebagai buku teks paling sukses dan berpengaruh sepanjang masa,<ref>{{Harv|Boyer|1991|loc="Euclid dari Alexandria" p. 119}}</ref> diperkenalkan [[ketelitian matematika]] melalui [[metode aksiomatik]] dan merupakan contoh paling awal dari format yang masih digunakan dalam matematika saat ini, bahwa definisi, aksioma, teorema, dan bukti. Meskipun sebagian besar konten '' Elemen '' sudah diketahui, Euclid mengatur menjadi satu kerangka kerja logis yang koheran.<ref name="Boyer 1991 loc=Euclid of Alexandria p. 104">{{Harv|Boyer|1991|loc="Euclid of Alexandria" p. 104}}</ref> ''Element'' diketahui oleh semua orang terpelajar di Barat hingga pertengahan abad ke 20 dan isinya masih diajarkan di kelas geometri hingga saat ini..<ref>Howard Eves, ''Pengantar Sejarah Matematika'', Saunders, 1990, {{ISBN|0-03-029558-0}} p. 141: "Tidak ada karya, kecuali [[Bible]], yang telah digunakan secara lebih luas...."</ref> [[Archimedes]] (c. 287–212 SM) dari [[Syracuse, Italy|Syracuse]] menggunakan [[metode|metode tersebut]] untuk menghitung [[luas]] di bawah busur dari [[parabola]] dengan [[Deret (matematika)|penjumlahan dari tak terhingga pada deret]], dan memberikan perkiraan yang sangat akurat dari [[Pi]].<ref>{{cite web | title = Sejarah kalkulus | author1 = O'Connor, J.J. | author2 = Robertson, E.F. | publisher = [[University of St Andrews]] | url = http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/The_rise_of_calculus.html | date = February 1996 | accessdate = 7 August 2007 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070715191704/http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/The_rise_of_calculus.html | archive-date = 15 July 2007 | url-status = live }}</ref> Dia juga mempelajari [[Archimedes spiral|spiral]] yang menyandang namanya dan memperoleh rumus untuk [[volume]] dari [[permukaan revolusi|permukaan revolusi]]. |

|||

[[Berkas:Woman teaching geometry.jpg|left|thumb|upright=.85|''Wanita mengajar geometri''. Ilustrasi di awal terjemahan abad pertengahan [[Euklides Element]], (c. 1310).]] |

|||

<!--[[Indian mathematics|Indian]] mathematicians also made many important contributions in geometry. The ''[[Satapatha Brahmana]]'' (3rd century BC) contains rules for ritual geometric constructions that are similar to the ''[[Shulba Sutras|Sulba Sutras]]''.<ref name="Staal 1999">{{Citation | last=Staal | first=Frits | author-link=Frits Staal | title=Greek and Vedic Geometry | journal=Journal of Indian Philosophy | volume=27 | issue=1–2 | year=1999 | pages=105–127 | doi=10.1023/A:1004364417713 }} |

|||

</ref> According to {{Harv|Hayashi|2005|p=363}}, the ''Śulba Sūtras'' contain "the earliest extant verbal expression of the Pythagorean Theorem in the world, although it had already been known to the Old Babylonians. They contain lists of [[Pythagorean triples]],<ref>Pythagorean triples are triples of integers <math> (a,b,c) </math> with the property: <math>a^2+b^2=c^2</math>. Thus, <math>3^2+4^2=5^2</math>, <math>8^2+15^2=17^2</math>, <math>12^2+35^2=37^2</math> etc.</ref> which are particular cases of [[Diophantine equations]].<ref name=cooke198>{{Harv|Cooke|2005|p=198}}: "The arithmetic content of the ''Śulva Sūtras'' consists of rules for finding Pythagorean triples such as (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (8, 15, 17), and (12, 35, 37). It is not certain what practical use these arithmetic rules had. The best conjecture is that they were part of religious ritual. A Hindu home was required to have three fires burning at three different altars. The three altars were to be of different shapes, but all three were to have the same area. These conditions led to certain "Diophantine" problems, a particular case of which is the generation of Pythagorean triples, so as to make one square integer equal to the sum of two others."</ref> |

|||

In the [[Bakhshali manuscript]], there is a handful of geometric problems (including problems about volumes of irregular solids). The Bakhshali manuscript also "employs a decimal place value system with a dot for zero."<ref name="hayashi2005-371">{{Harv|Hayashi|2005|p=371}}</ref> [[Aryabhata]]'s ''[[Aryabhatiya]]'' (499) includes the computation of areas and volumes. |

|||

[[Brahmagupta]] wrote his astronomical work ''[[Brahmasphutasiddhanta|{{IAST|Brāhma Sphuṭa Siddhānta}}]]'' in 628. Chapter 12, containing 66 [[Sanskrit]] verses, was divided into two sections: "basic operations" (including cube roots, fractions, ratio and proportion, and barter) and "practical mathematics" (including mixture, mathematical series, plane figures, stacking bricks, sawing of timber, and piling of grain).<ref name="hayashi2003-p121-122">{{Harv|Hayashi|2003|pp=121–122}}</ref> In the latter section, he stated his famous theorem on the diagonals of a [[cyclic quadrilateral]]. Chapter 12 also included a formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral (a generalization of [[Heron's formula]]), as well as a complete description of [[rational triangle]]s (''i.e.'' triangles with rational sides and rational areas).<ref name="hayashi2003-p121-122"/> |

|||

In the [[Middle Ages]], [[mathematics in medieval Islam]] contributed to the development of geometry, especially [[algebraic geometry]].<ref>R. Rashed (1994), ''The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and algebra'', p. 35 [[London]]</ref><ref>{{Harv|Boyer|1991|loc="The Arabic Hegemony" pp. 241–242}} "Omar Khayyam (c. 1050–1123), the "tent-maker," wrote an ''Algebra'' that went beyond that of al-Khwarizmi to include equations of third degree. Like his Arab predecessors, Omar Khayyam provided for quadratic equations both arithmetic and geometric solutions; for general cubic equations, he believed (mistakenly, as the 16th century later showed), arithmetic solutions were impossible; hence he gave only geometric solutions. The scheme of using intersecting conics to solve cubics had been used earlier by Menaechmus, Archimedes, and Alhazan, but Omar Khayyam took the praiseworthy step of generalizing the method to cover all third-degree equations (having positive roots). .. For equations of higher degree than three, Omar Khayyam evidently did not envision similar geometric methods, for space does not contain more than three dimensions, ... One of the most fruitful contributions of Arabic eclecticism was the tendency to close the gap between numerical and geometric algebra. The decisive step in this direction came much later with Descartes, but Omar Khayyam was moving in this direction when he wrote, "Whoever thinks algebra is a trick in obtaining unknowns has thought it in vain. No attention should be paid to the fact that algebra and geometry are different in appearance. Algebras are geometric facts which are proved."".</ref> [[Al-Mahani]] (b. 853) conceived the idea of reducing geometrical problems such as duplicating the cube to problems in algebra.<ref>{{MacTutor Biography|id=Al-Mahani|title=Al-Mahani}}</ref> [[Thābit ibn Qurra]] (known as Thebit in [[Latin]]) (836–901) dealt with [[arithmetic]] operations applied to [[ratio]]s of geometrical quantities, and contributed to the development of [[analytic geometry]].<ref name="ReferenceA"/> [[Omar Khayyám]] (1048–1131) found geometric solutions to [[cubic equation]]s.<ref>{{MacTutor Biography|id=Khayyam|title=Omar Khayyam}}</ref> The theorems of [[Ibn al-Haytham]] (Alhazen), Omar Khayyam and [[Nasir al-Din al-Tusi]] on [[quadrilateral]]s, including the [[Lambert quadrilateral]] and [[Saccheri quadrilateral]], were early results in [[hyperbolic geometry]], and along with their alternative postulates, such as [[Playfair's axiom]], these works had a considerable influence on the development of non-Euclidean geometry among later European geometers, including [[Witelo]] (c. 1230–c. 1314), [[Gersonides]] (1288–1344), [[Alfonso]], [[John Wallis]], and [[Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri]].<ref>Boris A. Rosenfeld and Adolf P. Youschkevitch (1996), "Geometry", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., ''[[Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science]]'', Vol. 2, pp. 447–494 [470], [[Routledge]], London and New York: {{quote|"Three scientists, Ibn al-Haytham, Khayyam, and al-Tusi, had made the most considerable contribution to this branch of geometry whose importance came to be completely recognized only in the 19th century. In essence, their propositions concerning the properties of quadrangles which they considered, assuming that some of the angles of these figures were acute of obtuse, embodied the first few theorems of the hyperbolic and the elliptic geometries. Their other proposals showed that various geometric statements were equivalent to the Euclidean postulate V. It is extremely important that these scholars established the mutual connection between this postulate and the sum of the angles of a triangle and a quadrangle. By their works on the theory of parallel lines Arab mathematicians directly influenced the relevant investigations of their European counterparts. The first European attempt to prove the postulate on parallel lines – made by Witelo, the Polish scientists of the 13th century, while revising Ibn al-Haytham's ''[[Book of Optics]]'' (''Kitab al-Manazir'') – was undoubtedly prompted by Arabic sources. The proofs put forward in the 14th century by the Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson, who lived in southern France, and by the above-mentioned Alfonso from Spain directly border on Ibn al-Haytham's demonstration. Above, we have demonstrated that ''Pseudo-Tusi's Exposition of Euclid'' had stimulated both J. Wallis's and G. Saccheri's studies of the theory of parallel lines."}}</ref> |

|||

In the early 17th century, there were two important developments in geometry. The first was the creation of analytic geometry, or geometry with [[Coordinate system|coordinates]] and [[equation]]s, by [[René Descartes]] (1596–1650) and [[Pierre de Fermat]] (1601–1665).<ref name="Boyer2012">{{cite book|author=Carl B. Boyer|title=History of Analytic Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2T4i5fXZbOYC|date=2012|publisher=Courier Corporation|isbn=978-0-486-15451-0}}</ref> This was a necessary precursor to the development of [[calculus]] and a precise quantitative science of [[physics]].<ref name="Edwards2012">{{cite book|author=C.H. Edwards Jr.|title=The Historical Development of the Calculus|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ilrlBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA95|date=2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4612-6230-5|page=95}}</ref> The second geometric development of this period was the systematic study of [[projective geometry]] by [[Girard Desargues]] (1591–1661).<ref name="FieldGray2012">{{cite book|author1=Judith V. Field|author2=Jeremy Gray|title=The Geometrical Work of Girard Desargues|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zSvSBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA43|year=2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4613-8692-6|page=43}}</ref> Projective geometry studies properties of shapes which are unchanged under [[projection (linear algebra)|projections]] and [[section (fiber bundle)|sections]], especially as they relate to [[perspective (graphical)|artistic perspective]].<ref name="Wylie2011">{{cite book|author=C. R. Wylie|title=Introduction to Projective Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VVvGc8kaajEC|date=2011|publisher=Courier Corporation|isbn=978-0-486-14170-1}}</ref> |

|||

Two developments in geometry in the 19th century changed the way it had been studied previously.<ref name="Gray2011">{{cite book|author=Jeremy Gray|title=Worlds Out of Nothing: A Course in the History of Geometry in the 19th Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3UeSCvazV0QC|date=2011|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-0-85729-060-1}}</ref> These were the discovery of [[non-Euclidean geometry|non-Euclidean geometries]] by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, János Bolyai and Carl Friedrich Gauss and of the formulation of [[symmetry]] as the central consideration in the [[Erlangen Programme]] of [[Felix Klein]] (which generalized the Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries). Two of the master geometers of the time were [[Bernhard Riemann]] (1826–1866), working primarily with tools from [[mathematical analysis]], and introducing the [[Riemann surface]], and [[Henri Poincaré]], the founder of [[algebraic topology]] and the geometric theory of [[dynamical system]]s. As a consequence of these major changes in the conception of geometry, the concept of "space" became something rich and varied, and the natural background for theories as different as [[complex analysis]] and [[classical mechanics]].<ref name="Bayro-Corrochano2018">{{cite book|author=Eduardo Bayro-Corrochano|title=Geometric Algebra Applications Vol. I: Computer Vision, Graphics and Neurocomputing|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SSVhDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA4|date=2018|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-319-74830-6|page=4}}</ref>--> |

|||

== Konsep penting dalam geometri == |

|||

Berikut ini adalah beberapa konsep terpenting dalam geometri.<ref name="Tabak 2014 xiv"/><ref name="Schmidt, W. 2002"/><ref name="Kline1990">{{cite book|author=Morris Kline|title=Pemikiran Matematika Dari Zaman Kuno ke Modern: Volume 3|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8YaBuGcmLb0C&pg=PA1010|date=Maret 1990|publisher=Oxford University Press, USA|isbn=978-0-19-506137-6|pages=1010–}}</ref> |

|||

=== Aksioma === |

|||

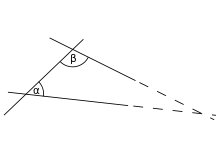

[[Berkas:Parallel postulate en.svg|thumb|right|Ilustrasi [[postulat paralel]] Euclid]] |

|||

{{Lihat pula|Geometri Euklides|Aksioma}} |

|||

[[Euclid]] mengambil pendekatan abstrak untuk geometri di [[Elemen Euklides|Elements]],<ref name="Katz2000">{{cite book|author=Victor J. Katz|title=Menggunakan Sejarah untuk Mengajar Matematika: Perspektif Internasional|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CbZ_YsdCmP0C&pg=PA45|date=21 September 2000|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-88385-163-0|pages=45–}}</ref> salah satu buku paling berpengaruh yang pernah ditulis.<ref name="Berlinski2014">{{cite book|author=David Berlinski|title=Raja Ruang Tak Terbatas: Euclid dan Elemen-elemennya|url=https://archive.org/details/kingofinfinitesp00davi|url-access=registration|date=8 April 2014|publisher=Basic Books|isbn=978-0-465-03863-3}}</ref> Euklides memperkenalkan [[aksioma]], atau [[postulat]] tertentu, yang mengekspresikan sifat utama atau bukti dengan sendirinya dari titik, garis, dan bidang.<ref name="Hartshorne2013">{{cite book|author=Robin Hartshorne|title=Geometri: Euclid and Beyond|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=C5fSBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA29|date=11 November 2013|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-0-387-22676-7|pages=29–}}</ref> Untuk melanjutkan untuk secara ketat menyimpulkan properti lain dengan penalaran matematika. Ciri khas pendekatan geometri Euclid adalah ketelitiannya, dan kemudian dikenal sebagai geometri ''aksiomatik'' atau ''[[geometri sintetik|sintetik]]''.<ref name="HerbstFujita2017">{{cite book|author1=Pat Herbst|author2=Taro Fujita|author3=Stefan Halverscheid|author4=Michael Weiss|title=Pembelajaran dan Pengajaran Geometri di Sekolah Menengah: Perspektif Modeling|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6DAlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA20|date=16 March 2017|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-1-351-97353-3|pages=20–}}</ref> Pada awal abad ke-19, penemuan [[geometri non-Euclidean]] oleh [[Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky]] (1792–1856), [[János Bolyai]] (1802–1860), [[Carl Friedrich Gauss]] (1777–1855) dan yang lainnya<ref name="Yaglom2012">{{cite book|author=I.M. Yaglom|title=Geometri Non-Euclidean Sederhana dan Dasar Fisiknya: Catatan Dasar Geometri Galilea dan Prinsip Relativitas Galilea|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FyToBwAAQBAJ&pg=PR6|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4612-6135-3|pages=6–}}</ref> menyebabkan kebangkitan minat dalam disiplin tersebut pada abad ke-20, [[David Hilbert]] (1862–1943) menggunakan penalaran aksiomatik dalam upaya untuk memberikan dasar geometri modern.<ref name="Holme2010">{{cite book|author=Audun Holme|title=Geometri: Warisan Budaya Kami|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zXwQGo8jyHUC&pg=PA254|date=23 September 2010|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-3-642-14441-7|pages=254–}}</ref> |

|||

===Titik=== |

|||

{{Main|Titik (geometri)}} |

|||

Titik yang dianggap sebagai objek fundamental dalam geometri Euclidean. Mereka telah didefinisikan dalam berbagai cara, termasuk definisi Euclid sebagai 'yang tidak memiliki bagian'<ref name=EuclidAll>''Elemen Euclid - Semua tiga belas buku dalam satu volume'', Berdasarkan terjemahan Heath, Green Lion Press {{ISBN|1-888009-18-7}}.</ref> dan melalui penggunaan aljabar atau set bersarang.<ref>{{cite journal |last= Clark|first=Bowman L. |date= Jan 1985|title= Individu dan Titik geometri|journal= Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic|volume= 26|issue=1 |pages= 61–75|doi= 10.1305/ndjfl/1093870761|doi-access= free}}</ref> Banyak bidang geometri, seperti geometri analitik, geometri diferensial, dan topologi, semua objek dianggap dibangun dari titik. Namun demikian, ada beberapa studi geometri tanpa mengacu pada titik.<ref>{{cite book|author=Gerla, G.|year=1995|chapter-url= http://www.dmi.unisa.it/people/gerla/www/Down/point-free.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110717210751/http://www.dmi.unisa.it/people/gerla/www/Down/point-free.pdf|archive-date=17 July 2011|chapter=Pointless Geometries|editor=Buekenhout, F.|editor2=Kantor, W.|title=Buku Pegangan geometri insiden: bangunan dan fondasi|publisher=North-Holland|pages=1015–1031}}</ref> |

|||

===Garis=== |

|||

{{main|Garis (geometri)}} |

|||

[[Euclid]] mendeskripsikan sebuah garis sebagai "panjang tanpa lebar" yang "terletak sama terhadap titik-titik pada dirinya sendiri".<ref name=EuclidAll /> Dalam matematika modern, mengingat banyaknya geometri, konsep garis terkait erat dengan cara menggambarkan geometri. Misalnya, dalam [[geometri analitik]], garis pada bidang sering didefinisikan sebagai himpunan titik yang koordinatnya memenuhi [[persamaan linier]] tertentu,<ref>{{cite book|author=[[John Casey (mathematician)|John Casey]]|year=1885|url= https://archive.org/details/cu31924001520455|title=Geometri Analitik Bagian Titik, Garis, Lingkaran, dan Kerucut}}</ref> tetapi dalam pengaturan yang lebih abstrak, seperti [[geometri kejadian]], garis mungkin merupakan objek independen, berbeda dari kumpulan titik yang terletak di atasnya.<ref>Buekenhout, Francis (1995), ''Buku Pegangan Geometri Insiden: Bangunan dan Fondasi'', Elsevier B.V.</ref> Dalam geometri diferensial, [[geodesik]] adalah generalisasi gagasan garis menjadi [[ruang melengkung]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/geodesic|title=geodesik - definisi geodesik dalam bahasa Inggris dari kamus Oxford|publisher=[[OxfordDictionaries.com]]|access-date=2016-01-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160715034047/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/geodesic|archive-date=15 July 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

===Bidang=== |

|||

{{main|Bidang (geometri)}} |

|||

<!--A [[plane (geometry)|plane]] is a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends infinitely far.<ref name= EuclidAll /> Planes are used in every area of geometry. For instance, planes can be studied as a [[surface (topology)|topological surface]] without reference to distances or angles;<ref name=Munkres>Munkres, James R. Topology. Vol. 2. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2000.</ref> it can be studied as an [[affine space]], where collinearity and ratios can be studied but not distances;<ref>Szmielew, Wanda. 'From affine to Euclidean geometry: An axiomatic approach.' Springer, 1983.</ref> it can be studied as the [[complex plane]] using techniques of [[complex analysis]];<ref>Ahlfors, Lars V. ''Complex analysis: an introduction to the theory of analytic functions of one complex variable.'' New York, London (1953).</ref> and so on.--> |

|||

===Sudut=== |

|||

{{main|Sudut}} |

|||

<!--[[Euclid]] defines a plane [[angle]] as the inclination to each other, in a plane, of two lines which meet each other, and do not lie straight with respect to each other.<ref name= EuclidAll /> In modern terms, an angle is the figure formed by two [[Ray (geometry)|rays]], called the ''sides'' of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the ''[[vertex (geometry)|vertex]]'' of the angle.<ref>{{SpringerEOM|id=Angle&oldid=13323|title=Angle|year=2001|last=Sidorov|first=L.A.}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Angle obtuse acute straight.svg|thumb|Acute (a), obtuse (b), and straight (c) angles. The acute and obtuse angles are also known as oblique angles.]] |

|||

In [[Euclidean geometry]], angles are used to study [[polygon]]s and [[triangle]]s, as well as forming an object of study in their own right.<ref name= EuclidAll /> The study of the angles of a triangle or of angles in a [[unit circle]] forms the basis of [[trigonometry]].<ref>Gelʹfand, Izrailʹ Moiseevič, and Mark Saul. "Trigonometry." 'Trigonometry'. Birkhäuser Boston, 2001. 1–20.</ref> |

|||

In [[differential geometry]] and [[calculus]], the angles between [[plane curve]]s or [[space curve]]s or [[surface (geometry)|surfaces]] can be calculated using the [[derivative (calculus)|derivative]].<ref name=Stewart>[[James Stewart (mathematician)|Stewart, James]] (2012). ''Calculus: Early Transcendentals'', 7th ed., Brooks Cole Cengage Learning. {{ISBN|978-0-538-49790-9}}</ref><ref>{{citation |last=Jost |first=Jürgen |title=Riemannian Geometry and Geometric Analysis |year=2002 |publisher=Springer-Verlag |location=Berlin |isbn=978-3-540-42627-1}}.</ref>--> |

|||

===Kurva=== |

|||

{{main|Kurva (geometri)}} |

|||

<!--A [[curve (geometry)|curve]] is a 1-dimensional object that may be straight (like a line) or not; curves in 2-dimensional space are called [[plane curve]]s and those in 3-dimensional space are called [[space curve]]s.<ref>Baker, Henry Frederick. Principles of geometry. Vol. 2. CUP Archive, 1954.</ref> |

|||

In topology, a curve is defined by a function from an interval of the real numbers to another space.<ref name = Munkres /> In differential geometry, the same definition is used, but the defining function is required to be differentiable <ref name = Carmo /> Algebraic geometry studies [[algebraic curve]]s, which are defined as [[algebraic varieties]] of [[dimension of an algebraic variety|dimension]] one.<ref name = mumford /> |

|||

===Permukaan=== |

|||

{{main|Permukaan (matematika)}} |

|||

[[Berkas:Sphere wireframe.svg|thumb|upright=0.85|Bola adalah permukaan yang dapat didefinisikan secara parametrik (dengan {{nowrap|''x'' {{=}} ''r'' sin ''θ'' cos ''φ'',}} {{nowrap|''y'' {{=}} ''r'' sin ''θ'' sin ''φ'',}} {{nowrap|''z'' {{=}} ''r'' cos ''θ'')}} atau secara implisit (by {{nowrap|''x''<sup>2</sup> + ''y''<sup>2</sup> + ''z''<sup>2</sup> − ''r''<sup>2</sup> {{=}} 0}}.)]] |

|||

<!--A [[surface (mathematics)|surface]] is a two-dimensional object, such as a sphere or paraboloid.<ref>Briggs, William L., and Lyle Cochran Calculus. "Early Transcendentals." {{ISBN|978-0321570567}}.</ref> In [[differential geometry]]<ref name=Carmo>Do Carmo, Manfredo Perdigao, and Manfredo Perdigao Do Carmo. Differential geometry of curves and surfaces. Vol. 2. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-hall, 1976.</ref> and [[topology]],<ref name=Munkres /> surfaces are described by two-dimensional 'patches' (or [[neighborhood (topology)|neighborhoods]]) that are assembled by [[diffeomorphism]]s or [[homeomorphism]]s, respectively. In algebraic geometry, surfaces are described by [[polynomial equation]]s.<ref name=mumford>{{cite book |last=Mumford |first=David |authorlink=David Mumford |title=The Red Book of Varieties and Schemes Includes the Michigan Lectures on Curves and Their Jacobians |edition=2nd |year=1999 |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer-Verlag]] |isbn=978-3-540-63293-1 |zbl=0945.14001}}</ref>--> |

|||

===Manifold=== |

|||

{{main|Manifold}} |

|||

<!--A [[manifold]] is a generalization of the concepts of curve and surface. In [[topology]], a manifold is a [[topological space]] where every point has a [[neighborhood (topology)|neighborhood]] that is [[homeomorphism|homeomorphic]] to Euclidean space.<ref name = Munkres /> In [[differential geometry]], a [[differentiable manifold]] is a space where each neighborhood is [[diffeomorphism|diffeomorphic]] to Euclidean space.<ref name=Carmo/> |

|||

Manifolds are used extensively in physics, including in [[general relativity]] and [[string theory]].<ref>Yau, Shing-Tung; Nadis, Steve (2010). The Shape of Inner Space: String Theory and the Geometry of the Universe's Hidden Dimensions. Basic Books. {{ISBN|978-0-465-02023-2}}.</ref>--> |

|||

===Panjang, luas, dan volume=== |

|||

{{main|Panjang|Luas|Volume}} |

|||

{{See also|Area#Daftar rumus|Volume#Rumus volume}} |

|||

<!--[[Length]], [[area]], and [[volume]] describe the size or extent of an object in one dimension, two dimension, and three dimensions respectively.<ref name="Treese2018">{{cite book|author=Steven A. Treese|title=History and Measurement of the Base and Derived Units|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bi1bDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA101|date=17 May 2018|publisher=Springer International Publishing|isbn=978-3-319-77577-7|pages=101–}}</ref> |

|||

In [[Euclidean geometry]] and [[analytic geometry]], the length of a line segment can often be calculated by the [[Pythagorean theorem]].<ref name="Cannon2017">{{cite book|author=James W. Cannon|title=Geometry of Lengths, Areas, and Volumes|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sSI_DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA11|date=16 November 2017|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-1-4704-3714-5|pages=11}}</ref> |

|||

Area and volume can be defined as fundamental quantities separate from length, or they can be described and calculated in terms of lengths in a plane or 3-dimensional space.<ref name="Treese2018"/> Mathematicians have found many explicit [[Area#List of formulas|formulas for area]] and [[Volume#Volume formulas|formulas for volume]] of various geometric objects. In [[calculus]], area and volume can be defined in terms of [[integral]]s, such as the [[Riemann integral]]<ref name="Strang1991">{{cite book|author=Gilbert Strang|title=Calculus|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OisInC1zvEMC|date=1 January 1991|publisher=SIAM|isbn=978-0-9614088-2-4}}</ref> or the [[Lebesgue integral]].<ref name="Bear2002">{{cite book|author=H. S. Bear|title=A Primer of Lebesgue Integration|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=__AmiGnEEewC|year=2002|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=978-0-12-083971-1}}</ref>--> |

|||

====Metrik dan ukuran==== |

|||

{{main|Metrik (matematika)|Ukur (matematika)}} |

|||

<!--[[File:Chinese pythagoras.jpg|thumb|right|Visual checking of the [[Pythagorean theorem]] for the (3, 4, 5) [[triangle]] as in the [[Zhoubi Suanjing]] 500–200 BC. The Pythagorean theorem is a consequence of the [[Euclidean metric]].]] |

|||

The concept of length or distance can be generalized, leading to the idea of [[metric space|metrics]].<ref>Dmitri Burago, [[Yuri Dmitrievich Burago|Yu D Burago]], Sergei Ivanov, ''A Course in Metric Geometry'', American Mathematical Society, 2001, {{ISBN|0-8218-2129-6}}.</ref> For instance, the [[Euclidean metric]] measures the distance between points in the [[Euclidean plane]], while the [[hyperbolic metric]] measures the distance in the [[hyperbolic plane]]. Other important examples of metrics include the [[Lorentz metric]] of [[special relativity]] and the semi-[[Riemannian metric]]s of [[general relativity]].<ref>{{Citation|last=Wald|first=Robert M.|authorlink=Robert Wald|title=General Relativity|publisher=University of Chicago Press|date=1984|isbn=978-0-226-87033-5|title-link=General Relativity (book)}}</ref> |

|||

In a different direction, the concepts of length, area and volume are extended by [[measure theory]], which studies methods of assigning a size or ''measure'' to [[Set (mathematics)|sets]], where the measures follow rules similar to those of classical area and volume.<ref name="Tao2011">{{cite book|author=Terence Tao|title=An Introduction to Measure Theory|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HoGDAwAAQBAJ|date=14 September 2011|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-0-8218-6919-2}}</ref> |

|||

===Congruence and similarity=== |

|||

{{main|Congruence (geometry)|Similarity (geometry)}} |

|||

[[Congruence (geometry)|Congruence]] and [[Similarity (geometry)|similarity]] are concepts that describe when two shapes have similar characteristics.<ref name="Libeskind2008">{{cite book|author=Shlomo Libeskind|title=Euclidean and Transformational Geometry: A Deductive Inquiry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=et6WMlkQlFcC&pg=PA255|date=12 February 2008|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|isbn=978-0-7637-4366-6|page=255}}</ref> In Euclidean geometry, similarity is used to describe objects that have the same shape, while congruence is used to describe objects that are the same in both size and shape.<ref name="Freitag2013">{{cite book|author=Mark A. Freitag|title=Mathematics for Elementary School Teachers: A Process Approach|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=G4BVGFiVKG0C&pg=PA614|date=1 January 2013|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=978-0-618-61008-2|page=614}}</ref> [[Hilbert]], in his work on creating a more rigorous foundation for geometry, treated congruence as an undefined term whose properties are defined by [[axiom]]s. |

|||

Congruence and similarity are generalized in [[transformation geometry]], which studies the properties of geometric objects that are preserved by different kinds of transformations.<ref name="Martin2012">{{cite book|author=George E. Martin|title=Transformation Geometry: An Introduction to Symmetry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gevlBwAAQBAJ|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4612-5680-9}}</ref>--> |

|||

===Konstruksi kompas dan pembatas=== |

|||

{{Main|Konstruksi kompas dan pembatas}} |

|||

<!--Classical geometers paid special attention to constructing geometric objects that had been described in some other way. Classically, the only instruments allowed in geometric constructions are the [[Compass (drafting)|compass]] and [[ruler|straightedge]]. Also, every construction had to be complete in a finite number of steps. However, some problems turned out to be difficult or impossible to solve by these means alone, and ingenious constructions using parabolas and other curves, as well as mechanical devices, were found.--> |

|||

===Dimensi=== |

|||

{{main|Dimensi}} |

|||

<!--[[File:Von Koch curve.gif|thumb|The [[Koch snowflake]], with [[fractal dimension]]=log4/log3 and [[topological dimension]]=1]] |

|||

Where the traditional geometry allowed dimensions 1 (a [[line (geometry)|line]]), 2 (a [[Plane (mathematics)|plane]]) and 3 (our ambient world conceived of as [[three-dimensional space]]), mathematicians and physicists have used [[higher dimension]]s for nearly two centuries.<ref name="Blacklock2018">{{cite book|author=Mark Blacklock|title=The Emergence of the Fourth Dimension: Higher Spatial Thinking in the Fin de Siècle|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nrNSDwAAQBAJ|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-875548-7}}</ref> One example of a mathematical use for higher dimensions is the [[configuration space (physics)|configuration space]] of a physical system, which has a dimension equal to the system's [[degrees of freedom]]. For instance, the configuration of a screw can be described by five coordinates.<ref name="Joly1895">{{cite book|author=Charles Jasper Joly|title=Papers|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cOTuAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA62|year=1895|publisher=The Academy|pages=62–}}</ref> |

|||

In [[general topology]], the concept of dimension has been extended from [[natural number]]s, to infinite dimension ([[Hilbert space]]s, for example) and positive [[real number]]s (in [[fractal geometry]]).<ref name="Temam2013">{{cite book|author=Roger Temam|title=Infinite-Dimensional Dynamical Systems in Mechanics and Physics|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OB_vBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA367|date=11 December 2013|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4612-0645-3|page=367}}</ref> In [[algebraic geometry]], the [[dimension of an algebraic variety]] has received a number of apparently different definitions, which are all equivalent in the most common cases.<ref name="JacobLam1994">{{cite book|author1=Bill Jacob|author2=Tsit-Yuen Lam|title=Recent Advances in Real Algebraic Geometry and Quadratic Forms: Proceedings of the RAGSQUAD Year, Berkeley, 1990-1991|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mHwcCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA111|year=1994|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-0-8218-5154-8|page=111}}</ref>--> |

|||

===Simetri=== |

|||

{{main |Simetri}} |

|||

<!--[[File:Order-3 heptakis heptagonal tiling.png|right|thumb|A [[Order-3 bisected heptagonal tiling|tiling]] of the [[Hyperbolic geometry|hyperbolic plane]]]] |

|||

The theme of [[symmetry]] in geometry is nearly as old as the science of geometry itself.<ref name="Stewart2008">{{cite book|author=Ian Stewart|title=Why Beauty Is Truth: A History of Symmetry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6akF1v7Ds3MC|date=29 April 2008|publisher=Basic Books|isbn=978-0-465-08237-7|page=14}}</ref> Symmetric shapes such as the [[circle]], [[regular polygon]]s and [[platonic solid]]s held deep significance for many ancient philosophers<ref name="Alexey2009">{{cite book|author=Stakhov Alexey|title=Mathematics Of Harmony: From Euclid To Contemporary Mathematics And Computer Science|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3k7ICgAAQBAJ&pg=PA144|date=11 September 2009|publisher=World Scientific|isbn=978-981-4472-57-9|page=144}}</ref> and were investigated in detail before the time of Euclid.<ref name="Hartshorne2013" /> Symmetric patterns occur in nature and were artistically rendered in a multitude of forms, including the graphics of [[da Vinci]], [[M.C. Escher]], and others.<ref name="Hahn1998">{{cite book|author=Werner Hahn|title=Symmetry as a Developmental Principle in Nature and Art|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wzhqDQAAQBAJ|year=1998|publisher=World Scientific|isbn=978-981-02-2363-2}}</ref> In the second half of the 19th century, the relationship between symmetry and geometry came under intense scrutiny. [[Felix Klein]]'s [[Erlangen program]] proclaimed that, in a very precise sense, symmetry, expressed via the notion of a transformation [[group (mathematics)|group]], determines what geometry ''is''.<ref name="Cantwell2002">{{cite book|author=Brian J. Cantwell|title=Introduction to Symmetry Analysis|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=76RS2ZQ0UyUC&pg=PR34|date=23 September 2002|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-139-43171-2|page=34}}</ref> Symmetry in classical [[Euclidean geometry]] is represented by [[Congruence (geometry)|congruences]] and rigid motions, whereas in [[projective geometry]] an analogous role is played by [[collineation]]s, [[geometric transformation]]s that take straight lines into straight lines.<ref name="RosenfeldWiebe2013">{{cite book|author1=B. Rosenfeld|author2=Bill Wiebe|title=Geometry of Lie Groups|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mIjSBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA158|date=9 March 2013|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4757-5325-7|pages=158ff}}</ref> However it was in the new geometries of Bolyai and Lobachevsky, Riemann, [[William Kingdon Clifford|Clifford]] and Klein, and [[Sophus Lie]] that Klein's idea to 'define a geometry via its [[symmetry group]]' found its inspiration.<ref name="Pesic2007" /> Both discrete and continuous symmetries play prominent roles in geometry, the former in [[topology]] and [[geometric group theory]],<ref name="Kaku2012">{{cite book|author=Michio Kaku|title=Strings, Conformal Fields, and Topology: An Introduction|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pM8FCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA151|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4684-0397-8|page=151}}</ref><ref name="BestvinaSageev2014">{{cite book|author1=Mladen Bestvina|author2=Michah Sageev|author3=Karen Vogtmann|title=Geometric Group Theory|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RGz1BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA132|date=24 December 2014|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-1-4704-1227-2|page=132}}</ref> the latter in [[Lie theory]] and [[Riemannian geometry]].<ref name="Steeb1996">{{cite book|author=W-H. Steeb|title=Continuous Symmetries, Lie Algebras, Differential Equations and Computer Algebra|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rZBIDQAAQBAJ|date=30 September 1996|publisher=World Scientific Publishing Company|isbn=978-981-310-503-4}}</ref><ref name="Misner2005">{{cite book|author=Charles W. Misner|title=Directions in General Relativity: Volume 1: Proceedings of the 1993 International Symposium, Maryland: Papers in Honor of Charles Misner|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zpGZwmTJZIUC&pg=PA272|date=20 October 2005|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-02139-5|pages=272}}</ref> |

|||

A different type of symmetry is the principle of [[Duality (projective geometry)|duality]] in [[projective geometry]], among other fields. This meta-phenomenon can roughly be described as follows: in any [[theorem]], exchange ''point'' with ''plane'', ''join'' with ''meet'', ''lies in'' with ''contains'', and the result is an equally true theorem.<ref name="Dowling1917">{{cite book|author=Linnaeus Wayland Dowling|title=Projective Geometry|url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924001523897|year=1917|publisher=McGraw-Hill book Company, Incorporated|page=[https://archive.org/details/cu31924001523897/page/n29 10]}}</ref> A similar and closely related form of duality exists between a [[vector space]] and its [[dual space]].<ref name="Gierz2006">{{cite book|author=G. Gierz|title=Bundles of Topological Vector Spaces and Their Duality|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2ml6CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA252|date=15 November 2006|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-540-39437-2|page=252}}</ref> |

|||

==Contemporary geometry== |

|||

===Euclidean geometry=== |

|||

{{main|Euclidean geometry}} |

|||

[[Euclidean geometry]] is geometry in its classical sense.<ref name="ButtsBrown2012">{{cite book|author1=Robert E. Butts|author2=J.R. Brown|title=Constructivism and Science: Essays in Recent German Philosophy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vzTqCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA127|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-94-009-0959-5|pages=127–}}</ref> As it models the space of the physical world, it is used in many scientific areas, such as [[mechanics]], [[astronomy]], [[crystallography]],<ref>{{cite book|title=Science|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xfNRAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA181|year=1886|publisher=Moses King|pages=181–}}</ref> and many technical fields, such as [[engineering]],<ref name="Abbot2013">{{cite book|author=W. Abbot|title=Practical Geometry and Engineering Graphics: A Textbook for Engineering and Other Students|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1LDsCAAAQBAJ&pg=PP6|date=11 November 2013|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-94-017-2742-6|pages=6–}}</ref> [[architecture]],<ref name="HerseyHersey2001">{{cite book|author1=George L. Hersey|title=Architecture and Geometry in the Age of the Baroque|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F1Tl9ok-7_IC|date=March 2001|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-32783-9}}</ref> [[geodesy]],<ref name="VanícekKrakiwsky2015">{{cite book|author1=P. Vanícek|author2=E.J. Krakiwsky|title=Geodesy: The Concepts|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1Mz-BAAAQBAJ|date=3 June 2015|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=978-1-4832-9079-9|page=23}}</ref> [[aerodynamics]],<ref name="CummingsMorton2015">{{cite book|author1=Russell M. Cummings|author2=Scott A. Morton|author3=William H. Mason|author4=David R. McDaniel|title=Applied Computational Aerodynamics|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gwzUBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA449|date=27 April 2015|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-05374-8|page=449}}</ref> and [[navigation]].<ref name="Williams1998">{{cite book|author=Roy Williams|title=Geometry of Navigation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yNzf7OKGLxIC|year=1998|publisher=Horwood Pub.|isbn=978-1-898563-46-4}}</ref> The mandatory educational curriculum of the majority of nations includes the study of Euclidean concepts such as [[point (geometry)|points]], [[Line (geometry)|lines]], [[plane (mathematics)|planes]], [[angle]]s, [[triangle]]s, [[congruence (geometry)|congruence]], [[similarity (geometry)|similarity]], [[solid figure]]s, [[circle]]s, and [[analytic geometry]].<ref name="Schmidt, W. 2002">Schmidt, W., Houang, R., & Cogan, L. (2002). "A coherent curriculum". ''American Educator'', 26(2), 1–18.</ref> |

|||

===Differential geometry=== |

|||

[[File:Hyperbolic triangle.svg|thumb|upright=1|right|[[Differential geometry]] uses tools from [[calculus]] to study problems involving curvature.]] |

|||

{{main | Differential geometry}} |

|||

[[Differential geometry]] uses techniques of [[calculus]] and [[linear algebra]] to study problems in geometry.<ref name="Walschap2015">{{cite book|author=Gerard Walschap|title=Multivariable Calculus and Differential Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cXPyCQAAQBAJ|date=1 July 2015|publisher=De Gruyter|isbn=978-3-11-036954-0}}</ref> It has applications in [[physics]],<ref name="Flanders2012">{{cite book|author=Harley Flanders|title=Differential Forms with Applications to the Physical Sciences|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U_GLN1eOKaMC|date=26 April 2012|publisher=Courier Corporation|isbn=978-0-486-13961-6}}</ref> [[econometrics]],<ref name="MarriottSalmon2000">{{cite book|author1=Paul Marriott|author2=Mark Salmon|title=Applications of Differential Geometry to Econometrics|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1Jjm4I5tqkUC|date=31 August 2000|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-65116-5}}</ref> and [[bioinformatics]],<ref name="HePetoukhov2011">{{cite book|author1=Matthew He|author2=Sergey Petoukhov|title=Mathematics of Bioinformatics: Theory, Methods and Applications|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Skov-LJ1mmQC&pg=PA106|date=16 March 2011|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-118-09952-0|page=106}}</ref> among others. |

|||

In particular, differential geometry is of importance to [[mathematical physics]] due to [[Albert Einstein]]'s [[general relativity]] postulation that the [[universe]] is [[curvature|curved]].<ref name="Dirac2016">{{cite book|author=P.A.M. Dirac|title=General Theory of Relativity|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qkWPDAAAQBAJ|date=10 August 2016|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-1-4008-8419-3}}</ref> Differential geometry can either be ''intrinsic'' (meaning that the spaces it considers are [[smooth manifold]]s whose geometric structure is governed by a [[Riemannian metric]], which determines how distances are measured near each point) or ''extrinsic'' (where the object under study is a part of some ambient flat Euclidean space).<ref name="AyJost2017">{{cite book|author1=Nihat Ay|author2=Jürgen Jost|author3=Hông Vân Lê|author4=Lorenz Schwachhöfer|title=Information Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pLsyDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA185|date=25 August 2017|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-319-56478-4|page=185}}</ref>--> |

|||

====Geometri non-Euklides==== |

|||

{{main|Geometri non-Euklides}} |

|||

<!--Euclidean geometry was not the only historical form of geometry studied. [[Spherical geometry]] has long been used by astronomers, astrologers, and navigators.<ref name="Rosenfeld2012">{{cite book|author=Boris A. Rosenfeld|title=A History of Non-Euclidean Geometry: Evolution of the Concept of a Geometric Space|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3wzSBwAAQBAJ|date=8 September 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4419-8680-1}}</ref> |

|||

[[Immanuel Kant]] argued that there is only one, ''absolute'', geometry, which is known to be true ''a priori'' by an inner faculty of mind: Euclidean geometry was [[synthetic a priori]].<ref>Kline (1972) "Mathematical thought from ancient to modern times", Oxford University Press, p. 1032. Kant did not reject the logical (analytic a priori) ''possibility'' of non-Euclidean geometry, see [[Jeremy Gray]], "Ideas of Space Euclidean, Non-Euclidean, and Relativistic", Oxford, 1989; p. 85. Some have implied that, in light of this, Kant had in fact ''predicted'' the development of non-Euclidean geometry, cf. Leonard Nelson, "Philosophy and Axiomatics," Socratic Method and Critical Philosophy, Dover, 1965, p. 164.</ref> This view was at first somewhat challenged by thinkers such as [[Saccheri]], then finally overturned by the revolutionary discovery of [[non-Euclidean geometry]] in the works of Bolyai, Lobachevsky, and Gauss (who never published his theory).<ref name="Sommerville1919">{{cite book|author=Duncan M'Laren Young Sommerville|title=Elements of Non-Euclidean Geometry ...|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6eASAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA15|year=1919|publisher=Open Court|pages=15ff}}</ref> They demonstrated that ordinary [[Euclidean space]] is only one possibility for development of geometry. A broad vision of the subject of geometry was then expressed by [[Riemann]] in his 1867 inauguration lecture ''Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen'' (''On the hypotheses on which geometry is based''),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.maths.tcd.ie/pub/HistMath/People/Riemann/Geom/ |title=Ueber die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160318034045/http://www.maths.tcd.ie/pub/HistMath/People/Riemann/Geom/ |archivedate=18 March 2016 |df= }}</ref> published only after his death. Riemann's new idea of space proved crucial in [[Albert Einstein]]'s [[general relativity theory]]. [[Riemannian geometry]], which considers very general spaces in which the notion of length is defined, is a mainstay of modern geometry.<ref name="Pesic2007">{{cite book|author=Peter Pesic|title=Beyond Geometry: Classic Papers from Riemann to Einstein|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z67x6IOuOUAC|date=1 January 2007|publisher=Courier Corporation|isbn=978-0-486-45350-7}}</ref>--> |

|||

===Topologi=== |

|||

{{main|Topologi}} |

|||

<!--[[File:Trefoil knot arb.png|thumb|right|A thickening of the [[trefoil knot]]]] |

|||

[[Topology]] is the field concerned with the properties of [[continuous mapping]]s,<ref name="Crossley2011">{{cite book|author=Martin D. Crossley|title=Essential Topology|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QhCgVrLHlLgC|date=11 February 2011|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-85233-782-7}}</ref> and can be considered a generalization of Euclidean geometry.<ref name="NashSen1988">{{cite book|author1=Charles Nash|author2=Siddhartha Sen|title=Topology and Geometry for Physicists|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nnnNCgAAQBAJ|date=4 January 1988|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=978-0-08-057085-3|page = 1}}</ref> In practice, topology often means dealing with large-scale properties of spaces, such as [[connectedness]] and [[compact (topology)|compactness]].<ref name=Munkres /> |

|||

The field of topology, which saw massive development in the 20th century, is in a technical sense a type of [[transformation geometry]], in which transformations are [[homeomorphism]]s.<ref name="Martin1996">{{cite book|author=George E. Martin|title=Transformation Geometry: An Introduction to Symmetry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KW4EwONsQJgC|date=20 December 1996|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-0-387-90636-2}}</ref> This has often been expressed in the form of the saying 'topology is rubber-sheet geometry'. Subfields of topology include [[geometric topology]], [[differential topology]], [[algebraic topology]] and [[general topology]].<ref name="May1999">{{cite book|author=J. P. May|title=A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g8SG03R1bpgC|date=September 1999|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-51183-2}}</ref> |

|||

===Geometri aljabar=== |

|||

{{main|Geometri aljabar}} |

|||

<!--[[File:Calabi yau.jpg|thumb|Quintic [[Calabi–Yau manifold|Calabi–Yau threefold]]]] |

|||

The field of [[algebraic geometry]] developed from the [[Cartesian geometry]] of [[co-ordinates]].<ref name="inc1905">{{cite book|title=The Encyclopedia Americana: A Universal Reference Library Comprising the Arts and Sciences, Literature, History, Biography, Geography, Commerce, Etc., of the World|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EGEMAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT489|year=1905|publisher=Scientific American Compiling Department|pages=489–}}</ref> It underwent periodic periods of growth, accompanied by the creation and study of [[projective geometry]], [[birational geometry]], [[algebraic variety|algebraic varieties]], and [[commutative algebra]], among other topics.<ref name="Dieudonne1985">{{cite book|author=Suzanne C. Dieudonne|title=History Algebraic Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_uhlf38jOrgC|date=30 May 1985|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-0-412-99371-8}}</ref> From the late 1950s through the mid-1970s it had undergone major foundational development, largely due to work of [[Jean-Pierre Serre]] and [[Alexander Grothendieck]].<ref name="Dieudonne1985" /> This led to the introduction of [[scheme (algebraic geometry)|schemes]] and greater emphasis on [[algebraic topology|topological]] methods, including various [[cohomology theory|cohomology theories]]. One of seven [[Millennium Prize problems]], the [[Hodge conjecture]], is a question in algebraic geometry.<ref name="CarlsonCarlson2006">{{cite book|author1=James Carlson|author2=James A. Carlson|author3=Arthur Jaffe|author4=Andrew Wiles|title=The Millennium Prize Problems|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7wJIPJ80RdUC|year=2006|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-0-8218-3679-8}}</ref> [[Wiles' proof of Fermat's Last Theorem]] uses advanced methods of algebraic geometry for solving a long-standing problem of [[number theory]]. |

|||

In general, algebraic geometry studies geometry through the use of concepts in [[commutative algebra]] such as [[multivariate polynomial]]s.<ref name="AHartshorne2013">{{cite book|author=Robin Hartshorne|title=Algebraic Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7z4mBQAAQBAJ|date=29 June 2013|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4757-3849-0}}</ref> It has applications in many areas, including [[cryptography]]<ref name="HoweLauter2017">{{cite book|author1=Everett W. Howe|author2=Kristin E. Lauter|author3=Judy L. Walker|title=Algebraic Geometry for Coding Theory and Cryptography: IPAM, Los Angeles, CA, February 2016|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bPM-DwAAQBAJ|date=15 November 2017|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-319-63931-4}}</ref> and [[string theory]].<ref name="MarinoThaddeus2008">{{cite book|author1=Marcos Marino|author2=Michael Thaddeus|author3=Ravi Vakil|title=Enumerative Invariants in Algebraic Geometry and String Theory: Lectures given at the C.I.M.E. Summer School held in Cetraro, Italy, June 6-11, 2005|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mb1qCQAAQBAJ|date=15 August 2008|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-540-79814-9}}</ref>--> |

|||

===Geometri kompleks=== |

|||

{{Main|Geometri kompleks}} |

|||

<!--[[Complex geometry]] studies the nature of geometric structures modelled on, or arising out of, the [[complex plane]].<ref>Huybrechts, D. (2006). Complex geometry: an introduction. Springer Science & Business Media. |

|||

</ref><ref>Griffiths, P., & Harris, J. (2014). Principles of algebraic geometry. John Wiley & Sons.</ref><ref>Wells, R. O. N., & García-Prada, O. (1980). Differential analysis on complex manifolds (Vol. 21980). New York: Springer.</ref> Complex geometry lies at the intersection of differential geometry, algebraic geometry, and analysis of [[several complex variables]], and has found applications to [[string theory]] and [[Mirror symmetry (string theory)|mirror symmetry]].<ref> |

|||

Hori, K., Thomas, R., Katz, S., Vafa, C., Pandharipande, R., Klemm, A., ... & Zaslow, E. (2003). Mirror symmetry (Vol. 1). American Mathematical Soc.</ref> |

|||

Complex geometry first appeared as a distinct area of study in the work of [[Bernhard Riemann]] in his study of [[Riemann surface]]s.<ref>Forster, O. (2012). Lectures on Riemann surfaces (Vol. 81). Springer Science & Business Media. |

|||

</ref><ref>Miranda, R. (1995). Algebraic curves and Riemann surfaces (Vol. 5). American Mathematical Soc.</ref><ref>Donaldson, S. (2011). Riemann surfaces. Oxford University Press.</ref> Work in the spirit of Riemann was carried out by the [[Italian school of algebraic geometry]] in the early 1900s. Contemporary treatment of complex geometry began with the work of [[Jean-Pierre Serre]], who introduced the concept of [[sheaf (mathematics)|sheaves]] to the subject, and illuminated the relations between complex geometry and algebraic geometry.<ref>Serre, J. P. (1955). Faisceaux algébriques cohérents. Annals of Mathematics, 197-278.</ref><ref>Serre, J. P. (1956). Géométrie algébrique et géométrie analytique. In Annales de l'Institut Fourier (Vol. 6, pp. 1-42).</ref> |

|||

The primary objects of study in complex geometry are [[complex manifold]]s, [[complex algebraic varieties]], and [[complex analytic varieties]], and [[holomorphic vector bundles]] and [[coherent sheaves]] over these spaces. Special examples of spaces studied in complex geometry include Riemann surfaces, and [[Calabi-Yau manifold]]s, and these spaces find uses in string theory. In particular, [[worldsheet]]s of strings are modelled by Riemann surfaces, and [[superstring theory]] predicts that the extra 6 dimensions of 10 dimensional [[spacetime]] may be modelled by Calabi-Yau manifolds.--> |

|||

===Geometri diskrit=== |

|||

{{main|Geometri diskrit}} |

|||

<!--[[File:Closepacking.svg|thumb|Discrete geometry includes the study of various [[sphere packing]]s.]] |

|||

[[Discrete geometry]] is a subject that has close connections with [[convex geometry]].<ref name="Matoušek2013">{{cite book|author=Jiří Matoušek|title=Lectures on Discrete Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K0fhBwAAQBAJ|date=1 December 2013|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4613-0039-7}}</ref><ref name="Zong2006">{{cite book|author=Chuanming Zong|title=The Cube-A Window to Convex and Discrete Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ola6htFUQ1IC|date=2 February 2006|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-85535-8}}</ref><ref name="Gruber2007">{{cite book|author=Peter M. Gruber|title=Convex and Discrete Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bSZKAAAAQBAJ|date=17 May 2007|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-3-540-71133-9}}</ref> It is concerned mainly with questions of relative position of simple geometric objects, such as points, lines and circles. Examples include the study of [[sphere packing]]s, [[triangulation (geometry)|triangulations]], the Kneser-Poulsen conjecture, etc.<ref name="DevadossO'Rourke2011">{{cite book|author1=Satyan L. Devadoss|author2=Joseph O'Rourke|title=Discrete and Computational Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=InJL6iAaIQQC|date=11 April 2011|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-1-4008-3898-1}}</ref><ref name="Bezdek2010">{{cite book|author=Károly Bezdek|title=Classical Topics in Discrete Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Tov0d9VMOfMC|date=23 June 2010|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4419-0600-7}}</ref> It shares many methods and principles with [[combinatorics]].--> |

|||

===Geometri komputasi=== |

|||

{{main|Geometri komputasi}} |

|||

<!--[[Computational geometry]] deals with [[algorithm]]s and their [[implementation (computer science)|implementations]] for manipulating geometrical objects. Important problems historically have included the [[travelling salesman problem]], [[minimum spanning tree]]s, [[hidden-line removal]], and [[linear programming]].<ref name="PreparataShamos2012">{{cite book|author1=Franco P. Preparata|author2=Michael I. Shamos|title=Computational Geometry: An Introduction|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_p3eBwAAQBAJ|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4612-1098-6}}</ref> |

|||

Although being a young area of geometry, it has many applications in [[computer vision]], [[image processing]], [[computer-aided design]], [[medical imaging]], etc.<ref name="GuYau2008">{{cite book|author1=Xianfeng David Gu|author2=Shing-Tung Yau|title=Computational Conformal Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4FDvAAAAMAAJ|year=2008|publisher=International Press|isbn=978-1-57146-171-1}}</ref> |

|||

===Teori grup geometris=== |

|||

{{main|Geometric group theory}} |

|||

[[Image:Cayley graph of F2.svg|right|thumb|The Cayley graph of the [[free group]] on two generators ''a'' and ''b'']] |

|||

[[Geometric group theory]] uses large-scale geometric techniques to study [[finitely generated group]]s.<ref name="Löh2017">{{cite book|author=Clara Löh|title=Geometric Group Theory: An Introduction|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1AxEDwAAQBAJ|date=19 December 2017|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-319-72254-2}}</ref> It is closely connected to [[low-dimensional topology]], such as in [[Grigori Perelman]]'s proof of the [[Geometrization conjecture]], which included the proof of the [[Poincaré conjecture]], a [[Millennium Prize Problems|Millennium Prize Problem]].<ref name="MorganTian2014">{{cite book|author1=John Morgan|author2=Gang Tian|title=The Geometrization Conjecture|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qv2cAwAAQBAJ|date=21 May 2014|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-0-8218-5201-9}}</ref> |

|||

Geometric group theory often revolves around the [[Cayley graph]], which is a geometric representation of a group. Other important topics include [[quasi-isometry|quasi-isometries]], [[Gromov-hyperbolic group]]s, and [[right angled Artin group]]s.<ref name="Löh2017"/><ref name="Wise2012">{{cite book|author=Daniel T. Wise|title=From Riches to Raags: 3-Manifolds, Right-Angled Artin Groups, and Cubical Geometry: 3-manifolds, Right-angled Artin Groups, and Cubical Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GsTW5oQhRPkC|year=2012|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-0-8218-8800-1}}</ref> |

|||

===Convex geometry=== |

|||

{{main|Convex geometry}} |

|||

[[Convex geometry]] investigates [[convex set|convex]] shapes in the Euclidean space and its more abstract analogues, often using techniques of [[real analysis]] and [[discrete mathematics]].<ref name="Meurant2014">{{cite book|author=Gerard Meurant|title=Handbook of Convex Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M2viBQAAQBAJ|date=28 June 2014|publisher=Elsevier Science|isbn=978-0-08-093439-6}}</ref> It has close connections to [[convex analysis]], [[optimization]] and [[functional analysis]] and important applications in [[number theory]]. |

|||

Convex geometry dates back to antiquity.<ref name="Meurant2014"/> [[Archimedes]] gave the first known precise definition of convexity. The [[isoperimetric problem]], a recurring concept in convex geometry, was studied by the Greeks as well, including [[Zenodorus (mathematician)|Zenodorus]]. Archimedes, [[Plato]], [[Euclid]], and later [[Kepler]] and [[Coxeter]] all studied [[convex polytope]]s and their properties. From the 19th century on, mathematicians have studied other areas of convex mathematics, including higher-dimensional polytopes, volume and surface area of convex bodies, [[Gaussian curvature]], [[algorithms]], [[tiling (geometry)|tilings]] and [[lattice (group)|lattice]]s.--> |

|||

==Aplikasi== |

|||

Geometri telah menemukan aplikasi di banyak bidang, beberapa di antaranya dijelaskan di bawah ini. |

|||

<!-- |

|||

<!--===Art=== |

|||

{{main |Mathematics and art}} |

|||

[[File:Fes Medersa Bou Inania Mosaique2.jpg|thumb|Bou Inania Madrasa, Fes, Morocco, zellige mosaic tiles forming elaborate geometric tessellations]] |

|||

Mathematics and art are related in a variety of ways. For instance, the theory of [[perspective (graphical)|perspective]] showed that there is more to geometry than just the metric properties of figures: perspective is the origin of [[projective geometry]].<ref name="Richter-Gebert2011">{{cite book|author=Jürgen Richter-Gebert|title=Perspectives on Projective Geometry: A Guided Tour Through Real and Complex Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F_NP8Kub2XYC|date=4 February 2011|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-3-642-17286-1}}</ref> |

|||

Artists have long used concepts of [[proportionality (mathematics)|proportion]] in design. [[Vitruvius]] developed a complicated theory of ''ideal proportions'' for the human figure.<ref name="Elam2001">{{cite book|author=Kimberly Elam|title=Geometry of Design: Studies in Proportion and Composition|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JXIEz2XYnp8C|year=2001|publisher=Princeton Architectural Press|isbn=978-1-56898-249-6}}</ref> These concepts have been used and adapted by artists from [[Michelangelo]] to modern comic book artists.<ref name="Guigar2004">{{cite book|author=Brad J. Guigar|title=The Everything Cartooning Book: Create Unique And Inspired Cartoons For Fun And Profit|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7gftDQAAQBAJ&pg=PT82|date=4 November 2004|publisher=Adams Media|isbn=978-1-4405-2305-2|pages=82–}}</ref> |

|||

The [[golden ratio]] is a particular proportion that has had a controversial role in art. Often claimed to be the most aesthetically pleasing ratio of lengths, it is frequently stated to be incorporated into famous works of art, though the most reliable and unambiguous examples were made deliberately by artists aware of this legend.<ref name="Livio2008">{{cite book|author=Mario Livio|title=The Golden Ratio: The Story of PHI, the World's Most Astonishing Number|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bUARfgWRH14C&pg=PA166|date=12 November 2008|publisher=Crown/Archetype|isbn=978-0-307-48552-6|page=166}}</ref> |

|||

[[Tiling (geometry)|Tilings]], or tessellations, have been used in art throughout history. [[Islamic art]] makes frequent use of tessellations, as did the art of [[Escher]].<ref name="EmmerSchattschneider2007">{{cite book|author1=Michele Emmer|author2=Doris Schattschneider|title=M.C. Escher's Legacy: A Centennial Celebration|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5DDyBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA107|date=8 May 2007|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-540-28849-7|page=107}}</ref> Escher's work also made use of [[hyperbolic geometry]]. |

|||

[[Cézanne]] advanced the theory that all images can be built up from the [[sphere]], the [[cone]], and the [[cylinder]]. This is still used in art theory today, although the exact list of shapes varies from author to author.<ref name="CapitoloSchwab2004">{{cite book|author1=Robert Capitolo|author2=Ken Schwab|title=Drawing Course 101|url=https://archive.org/details/drawingcourse1010000capi|url-access=registration|year=2004|publisher=Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.|isbn=978-1-4027-0383-6|page=[https://archive.org/details/drawingcourse1010000capi/page/22 22]}}</ref><ref name="Gelineau2011">{{cite book|author=Phyllis Gelineau|title=Integrating the Arts Across the Elementary School Curriculum|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1Ib0mUl_VhwC&pg=PA55|date=1 January 2011|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=978-1-111-30126-2|pages=55}}</ref> |

|||

===Architecture=== |

|||

{{main|Mathematics and architecture|Architectural geometry}} |

|||

Geometry has many applications in architecture. In fact, it has been said that geometry lies at the core of architectural design.<ref name="CeccatoHesselgren2016">{{cite book|author1=Cristiano Ceccato|author2=Lars Hesselgren|author3=Mark Pauly|author4=Helmut Pottmann, Johannes Wallner|title=Advances in Architectural Geometry 2010|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q45sDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA6|date=5 December 2016|publisher=Birkhäuser|isbn=978-3-99043-371-3|page=6}}</ref><ref name="Pottmann2007">{{cite book|author=Helmut Pottmann|title=Architectural geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bIceAQAAIAAJ|year=2007|publisher=Bentley Institute Press}}</ref> Applications of geometry to architecture include the use of [[projective geometry]] to create [[forced perspective]],<ref name="MoffettFazio2003">{{cite book|author1=Marian Moffett|author2=Michael W. Fazio|author3=Lawrence Wodehouse|title=A World History of Architecture|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IFMohetegAcC&pg=PT371|year=2003|publisher=Laurence King Publishing|isbn=978-1-85669-371-4|page=371}}</ref> the use of [[conic section]]s in constructing domes and similar objects,<ref name="HerseyHersey2001" /> the use of [[tessellations]],<ref name="HerseyHersey2001"/> and the use of symmetry.<ref name="HerseyHersey2001"/> |

|||

===Physics=== |

|||

{{main|Mathematical physics}} |

|||

The field of [[astronomy]], especially as it relates to mapping the positions of [[star]]s and [[planet]]s on the [[celestial sphere]] and describing the relationship between movements of celestial bodies, have served as an important source of geometric problems throughout history.<ref name="GreenGreen1985">{{cite book|author1=Robin M. Green|author2=Robin Michael Green|title=Spherical Astronomy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wOpaUFQFwTwC&pg=PA1|date=31 October 1985|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-31779-5|page=1}}</ref> |

|||

[[Riemannian geometry]] and [[pseudo-Riemannian]] geometry are used in [[general relativity]].<ref name="Alekseevskiĭ2008">{{cite book|author=Dmitriĭ Vladimirovich Alekseevskiĭ|title=Recent Developments in Pseudo-Riemannian Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K6-TgxMKu4QC|year=2008|publisher=European Mathematical Society|isbn=978-3-03719-051-7}}</ref> [[String theory]] makes use of several variants of geometry,<ref name="YauNadis2010">{{cite book|author1=Shing-Tung Yau|author2=Steve Nadis|title=The Shape of Inner Space: String Theory and the Geometry of the Universe's Hidden Dimensions|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M40Ytp8Os_gC|date=7 September 2010|publisher=Basic Books|isbn=978-0-465-02266-3}}</ref> as does [[quantum information theory]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Bengtsson |first1=Ingemar |last2=Życzkowski |first2=Karol |authorlink2=Karol Życzkowski |title=Geometry of Quantum States: An Introduction to Quantum Entanglement |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |edition=2nd |year=2017 |isbn=9781107026254 |oclc=1004572791}}</ref> |

|||

===Other fields of mathematics=== |

|||

[[File:Square root of 2 triangle.svg|thumb|right|The Pythagoreans discovered that the sides of a triangle could have [[Commensurability (mathematics)|incommensurable]] lengths.]] |

|||

[[Calculus]] was strongly influenced by geometry.<ref name="Boyer2012"/> For instance, the introduction of [[coordinates]] by [[René Descartes]] and the concurrent developments of [[algebra]] marked a new stage for geometry, since geometric figures such as [[plane curve]]s could now be represented [[analytic geometry|analytically]] in the form of functions and equations. This played a key role in the emergence of [[infinitesimal calculus]] in the 17th century. Analytic geometry continues to be a mainstay of pre-calculus and calculus curriculum.<ref name="FlandersPrice2014">{{cite book|author1=Harley Flanders|author2=Justin J. Price|title=Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5abiBQAAQBAJ|date=10 May 2014|publisher=Elsevier Science|isbn=978-1-4832-6240-6}}</ref><ref name="RogawskiAdams2015">{{cite book|author1=Jon Rogawski|author2=Colin Adams|title=Calculus|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OWeZBgAAQBAJ|date=30 January 2015|publisher=W. H. Freeman|isbn=978-1-4641-7499-5}}</ref> |

|||

Another important area of application is [[number theory]].<ref name="Lozano-Robledo2019">{{cite book|author=Álvaro Lozano-Robledo|title=Number Theory and Geometry: An Introduction to Arithmetic Geometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ESiODwAAQBAJ|date=21 March 2019|publisher=American Mathematical Soc.|isbn=978-1-4704-5016-8}}</ref> In [[ancient Greece]] the [[Pythagoreans]] considered the role of numbers in geometry. However, the discovery of incommensurable lengths contradicted their philosophical views.<ref name="Sangalli2009">{{cite book|author=Arturo Sangalli|title=Pythagoras' Revenge: A Mathematical Mystery|url=https://archive.org/details/pythagorasreveng0000sang|url-access=registration|date=10 May 2009|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-04955-7|page=[https://archive.org/details/pythagorasreveng0000sang/page/57 57]}}</ref> Since the 19th century, geometry has been used for solving problems in number theory, for example through the [[geometry of numbers]] or, more recently, [[scheme theory]], which is used in [[Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem]].<ref name="CornellSilverman2013">{{cite book|author1=Gary Cornell|author2=Joseph H. Silverman|author3=Glenn Stevens|title=Modular Forms and Fermat's Last Theorem|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jD3TBwAAQBAJ|date=1 December 2013|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-1-4612-1974-3}}</ref>--> |

|||

==Lihat pula== |

|||

===Daftar=== |

|||

* [[Daftar geometer]] |

|||

** [[:Kategori:Geometer aljabar]] |

|||

** [[:Kategori:Geometer Diferensial]] |

|||

** [[:Kategori:Geometer]] |

|||

** [[:Kategori:Ahli topologi]] |

|||

* [[Daftar rumus dalam geometri dasar]] |

|||

* [[Daftar topik geometri]] |

|||

* [[Daftar publikasi penting dalam matematika#Geometri|Daftar publikasi penting dalam geometri]] |

|||

* [[Daftar topik matematika]] |