Rashi: Perbedaan antara revisi

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

||

| Baris 32: | Baris 32: | ||

* (1) "Shlomo son of Rabbi Yitzhak," |

* (1) "Shlomo son of Rabbi Yitzhak," |

||

* (2) "Shlomo son of Yitzhak," |

* (2) "Shlomo son of Yitzhak," |

||

* (3) "Shlomo Yitzhaki," |

* (3) "Shlomo Yitzhaki," dan lain-lain.<ref>''Cybernetics and Systems'' Volume 42, Issue 3, pages 180-197 29 Apr 2011 Available online: {{doi|10.1080/01969722.2011.567893}} article authors Yaakov HaCohen-Kerner, Nadav Schweitzer & Dror Mughaz title ''Automatically Identifying Citations in Hebrew-Aramaic Documents'' published Taylor & Francis "For example, the Pardes book written by Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki, known by the abbreviation Rashi, can be cited using the following patterns: (1) "Shlomo son of Rabbi Yitzhak," (2) "Shlomo son of Yitzhak," (3) "Shlomo Yitzhaki," (4) "In the name of Rashi who wrote in the Pardes"</ref> |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

In older literature, Rashi is sometimes referred to as ''Jarchi'' or ''Yarhi'' ({{hebrew|ירחי}}), his abbreviated name being interpreted as '''R'''abbi '''Sh'''lomo '''Y'''arhi. This was understood to refer to the Hebrew name of [[Lunel]] in [[Provence]], popularly derived from the French ''lune'' "moon", in Hebrew {{hebrew|ירח}},<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=xpc9AAAAcAAJ&pg=PA74</ref> in which Rashi was assumed to have lived at some time<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=wlMBAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA2</ref> or to have been born, or where his ancestors were supposed to have originated.<ref>see for example http://books.google.com/books?id=KyJ44AeJj4sC&pg=PA233 http://books.google.com/books?id=gc4FAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA286</ref> [[Richard Simon]]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=3aQUAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA545</ref> and Johann Wilhelm Wolf<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=zQIVAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA1057</ref> claimed that only Christian scholars referred to Rashi as Jarchi, and that this epithet was unknown to the Jews. [[Bernardo de Rossi]], however, demonstrated that Hebrew scholars also referred to Rashi as Yarhi.<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=CQBbc1vhiysC&pg=PA337</ref> In 1839, [[Leopold Zunz]]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=b6EXAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA328</ref> showed that the Hebrew usage of Jarchi was an erroneous propagation of the error by Christian writers, instead interpreting the abbreviation as it is understood today: '''R'''abbi '''Sh'''lomo '''Y'''itchaki. In consequence, by the second half of the 19th century, the appellation ''Jarchi'' was considered obsolete.<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=IdcZAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA423</ref> The evolution of this term has been thoroughly traced.<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=Nsl2NrA6v6gC&pg=PA1 http://books.google.com/books?id=7DAHAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA643</ref> |

In older literature, Rashi is sometimes referred to as ''Jarchi'' or ''Yarhi'' ({{hebrew|ירחי}}), his abbreviated name being interpreted as '''R'''abbi '''Sh'''lomo '''Y'''arhi. This was understood to refer to the Hebrew name of [[Lunel]] in [[Provence]], popularly derived from the French ''lune'' "moon", in Hebrew {{hebrew|ירח}},<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=xpc9AAAAcAAJ&pg=PA74</ref> in which Rashi was assumed to have lived at some time<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=wlMBAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA2</ref> or to have been born, or where his ancestors were supposed to have originated.<ref>see for example http://books.google.com/books?id=KyJ44AeJj4sC&pg=PA233 http://books.google.com/books?id=gc4FAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA286</ref> [[Richard Simon]]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=3aQUAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA545</ref> and Johann Wilhelm Wolf<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=zQIVAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA1057</ref> claimed that only Christian scholars referred to Rashi as Jarchi, and that this epithet was unknown to the Jews. [[Bernardo de Rossi]], however, demonstrated that Hebrew scholars also referred to Rashi as Yarhi.<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=CQBbc1vhiysC&pg=PA337</ref> In 1839, [[Leopold Zunz]]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=b6EXAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA328</ref> showed that the Hebrew usage of Jarchi was an erroneous propagation of the error by Christian writers, instead interpreting the abbreviation as it is understood today: '''R'''abbi '''Sh'''lomo '''Y'''itchaki. In consequence, by the second half of the 19th century, the appellation ''Jarchi'' was considered obsolete.<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=IdcZAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA423</ref> The evolution of this term has been thoroughly traced.<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=Nsl2NrA6v6gC&pg=PA1 http://books.google.com/books?id=7DAHAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA643</ref> |

||

| Baris 71: | Baris 71: | ||

[[File:Rashi statue in troyes.jpg|thumb|Monumen peringatan Rashi di [[Troyes]], France]] |

[[File:Rashi statue in troyes.jpg|thumb|Monumen peringatan Rashi di [[Troyes]], France]] |

||

Rashi meninggal pada tanggal 13 Juli 1105 (29 [[Tammuz]] 4865) pada usia 65. Ia dimakamkan di Troyes. Lokasi pekuburannya dicatat dalam ''Seder ha-Dorot'' (''Seder Hadoros''), tetapi lambat laun lokasi tepatnya dilupakan. Beberapa tahun berselang, seorang profesor [[University of Paris]] (Sorbonne) menemukan peta kuno yang menggambarkan lokasi makam, sekarang menjadi taman terbuka kota Troyes. Setelah penemuan ini, orang Yahudi Perancis mendirikan suatu monumen besar di tengah taman itu, berupa sebuah bola dunia besar berwarna hitam dan putih dengan huruf-huruf Ibrani yang menonjol, ''[[Shin (huruf Ibrani)|Shin]]'' (ש) (yaitu untuk "Shlomo", nama depan Rashi). Pada landasan granit monumen tersebut diukir ''Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki — Commentator and Guide'' (Komentator dan Pemandu). |

Rashi meninggal pada tanggal 13 Juli 1105 (29 [[Tammuz]] 4865) pada usia 65 tahun. Ia dimakamkan di [[Troyes]], [[Perancis]]. Lokasi pekuburannya dicatat dalam ''Seder ha-Dorot'' (''Seder Hadoros''), tetapi lambat laun lokasi tepatnya dilupakan. Beberapa tahun berselang, seorang profesor [[University of Paris]] (Sorbonne) menemukan peta kuno yang menggambarkan lokasi makam, sekarang menjadi taman terbuka kota Troyes. Setelah penemuan ini, orang Yahudi Perancis mendirikan suatu monumen besar di tengah taman itu, berupa sebuah bola dunia besar berwarna hitam dan putih dengan huruf-huruf Ibrani yang menonjol, ''[[Shin (huruf Ibrani)|Shin]]'' (ש) (yaitu untuk "Shlomo", nama depan Rashi). Pada landasan granit monumen tersebut diukir ''Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki — Commentator and Guide'' (Komentator dan Pemandu). |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

In 2005, [[Yisroel Meir Gabbai]] erected an additional plaque at this site marking the square as a burial ground. The plaque reads: "''The place you are standing on is the cemetery of the town of Troyes. Many [[Rishonim]] are buried here, among them Rabbi Shlomo, known as Rashi the holy, may his merit protect us''".<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.chareidi.org/archives5765/mattos/MTS65features.htm |title=The Discovery of the Resting Places of Rashi and the Baalei Hatosfos |author=Y. Friedman| publisher=Dei'ah Vedibur |date=2005-07-25}}</ref> |

In 2005, [[Yisroel Meir Gabbai]] erected an additional plaque at this site marking the square as a burial ground. The plaque reads: "''The place you are standing on is the cemetery of the town of Troyes. Many [[Rishonim]] are buried here, among them Rabbi Shlomo, known as Rashi the holy, may his merit protect us''".<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.chareidi.org/archives5765/mattos/MTS65features.htm |title=The Discovery of the Resting Places of Rashi and the Baalei Hatosfos |author=Y. Friedman| publisher=Dei'ah Vedibur |date=2005-07-25}}</ref> |

||

| Baris 122: | Baris 122: | ||

===Criticism of Rashi=== |

===Criticism of Rashi=== |

||

Although Rashi’s interpretations were widely respected, there are many who criticize his work. After the 12th century, criticism on Rashi’s commentaries became common on Jewish works such as the Talmud. The criticisms mainly dealt with difficult passages. Generally Rashi provides the “pshat” or literal meaning of Jewish texts, while his disciples known as the Tosafot, criticized his work and gave more interpretative descriptions of the texts. The Tosafot’s commentaries can be found in Jewish texts opposite Rashi’s commentary. The Tosafot added comments and criticism in places were Rashi had not added comments. The Tosafot went beyond the passage itself in search of arguments, parallels, and distinctions that could be drawn out. This addition to Jewish texts was seen as causing a “major cultural product” <ref name="Bloomberg, Jon 2004">Bloomberg, Jon. The Jewish World in the Modern Age. Jersey City, NJ: KTAV Pub. House, 2004. 69.</ref> which became an important part of Torah study.<ref>"Tosafot." JewishEncyclopedia.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2013. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/14457-tosafot>.</ref><ref name="Bloomberg, Jon 2004"/> |

Although Rashi’s interpretations were widely respected, there are many who criticize his work. After the 12th century, criticism on Rashi’s commentaries became common on Jewish works such as the Talmud. The criticisms mainly dealt with difficult passages. Generally Rashi provides the “pshat” or literal meaning of Jewish texts, while his disciples known as the Tosafot, criticized his work and gave more interpretative descriptions of the texts. The Tosafot’s commentaries can be found in Jewish texts opposite Rashi’s commentary. The Tosafot added comments and criticism in places were Rashi had not added comments. The Tosafot went beyond the passage itself in search of arguments, parallels, and distinctions that could be drawn out. This addition to Jewish texts was seen as causing a “major cultural product” <ref name="Bloomberg, Jon 2004">Bloomberg, Jon. The Jewish World in the Modern Age. Jersey City, NJ: KTAV Pub. House, 2004. 69.</ref> which became an important part of Torah study.<ref>"Tosafot." JewishEncyclopedia.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2013. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/14457-tosafot>.</ref><ref name="Bloomberg, Jon 2004"/> |

||

--> |

|||

== |

== Peninggalan == |

||

[[File:Raschihaus.jpg|thumb|200px|''Raschihaus'', Jewish Museum, Worms, |

[[File:Raschihaus.jpg|thumb|200px|''Raschihaus'', Jewish Museum, Worms, Jerman.]] |

||

[[Komentari]] Rashi mengenai [[Talmud]] terus menjadi dasar kunci penelitian dan interpretasi rabbinik kontemporer. Tanpa tafsir Rashi, Talmud dianggap "buku yang tertutup". Dengan komentarinya, setiap pelajar yang telah diperkenalkan oleh gurunya untuk mempelajari, akan dapat terus belajar sendiri, menguraikan bahasa dan maknanya dengan pertolongan Rashi. |

|||

Rashi's commentary on the Talmud continues to be a key basis for contemporary rabbinic scholarship and interpretation. Without Rashi's commentary, the Talmud would have remained a closed book.{{Citation needed|date=July 2013}} With it, any student who has been introduced to its study by a teacher can continue learning on his own, deciphering its language and meaning with the aid of Rashi. |

|||

<!-- |

|||

The [[ArtScroll#Schottenstein Edition Talmud|Schottenstein Edition interlinear translation of the Talmud]] bases its English-language commentary primarily on Rashi, and describes his continuing importance as follows: {{quote|It has been our policy throughout the Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud to give Rashi's interpretation as the primary explanation of the [[Gemara]]. Since it is not possible in a work of this nature to do justice to all of the [[Rishonim]], we have chosen to follow the commentary most learned by people, and the one studied first by virtually all Torah scholars. In this we have followed the ways of our teachers and the Torah masters of the last nine hundred years, who have assigned a pride of place to Rashi's commentary and made it a point of departure for all other commentaries.<ref>''The Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud:Talmud Bavli:Tractate Nedarim. [[ArtScroll|Mesorah Publications Limited]], 2000 (General Introduction, unpaginated). (Note: The Schottenstein Edition editors explained further that they chose [[Nissim of Gerona|Ran]]'s commentary for [[Nedarim (tractate)|Tractate Nedarim]] as an exception, based on a belief that the commentary attributed to Rashi for this tractate was not written by Rashi)</ref>}} |

The [[ArtScroll#Schottenstein Edition Talmud|Schottenstein Edition interlinear translation of the Talmud]] bases its English-language commentary primarily on Rashi, and describes his continuing importance as follows: {{quote|It has been our policy throughout the Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud to give Rashi's interpretation as the primary explanation of the [[Gemara]]. Since it is not possible in a work of this nature to do justice to all of the [[Rishonim]], we have chosen to follow the commentary most learned by people, and the one studied first by virtually all Torah scholars. In this we have followed the ways of our teachers and the Torah masters of the last nine hundred years, who have assigned a pride of place to Rashi's commentary and made it a point of departure for all other commentaries.<ref>''The Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud:Talmud Bavli:Tractate Nedarim. [[ArtScroll|Mesorah Publications Limited]], 2000 (General Introduction, unpaginated). (Note: The Schottenstein Edition editors explained further that they chose [[Nissim of Gerona|Ran]]'s commentary for [[Nedarim (tractate)|Tractate Nedarim]] as an exception, based on a belief that the commentary attributed to Rashi for this tractate was not written by Rashi)</ref>}} |

||

Revisi per 18 Oktober 2013 16.31

| Rashi | |

|---|---|

Lukisan menggambarkan Rashi dari abad ke-16 | |

| Lahir | 22 Februari 1040 Troyes, Perancis |

| Meninggal | 13 Juli 1105 (umur 65) Troyes, Perancis |

| Makam | Troyes |

| Tempat tinggal | France |

| Kebangsaan | French |

| Dikenal atas | menulis tafsir Alkitab Ibrani |

Shlomo Yitzchaki (Ibrani: רבי שלמה יצחקי), atau dalam bahasa Latin Salomon Isaacides, dan sekarang umumnya dikenal dengan akronim Rashi (Ibrani: רש"י, RAbbi SHlomo Itzhaki; 22 Februari 1040 – 13 Juli 1105), adalah seorang rabbi Yahudi yang hidup di Perancis pada abad pertengahan. Ia sangat dihormati sebagai kontributor utama dari kalangan Yahudi Ashkenazi terhadap studi Taurat. Terkenal sebagai pengarang tafsir atau komentari komprehensif Talmud, juga tafsir komprehensif Tanakh (Alkitab Ibrani). Ia dianggap sebagai "bapa" semua tafsir Talmud sesudahnya (yaitu, Baalei Tosafot) dan "Tanach" (yaitu, Ramban, Ibn Ezra, Ohr HaChaim, dan lain-lain).[1][2]

Terkenal karena kemampuannya untuk memberikan makna dasar suatu teks dalam gaya ringkas dan lancar. Karenanya tulisan-tulisan Rashi menarik bagi pakar terpelajar maupun murid-murid yang baru mulai. Karya-karyanya terus menjadi pusat untuk studi Yahudi kontemporer. Komentari atau tafir mengenai Talmud, yang meliputi hampir seluruh Talmud Babel (total 30 traktat), telah dimasukkan dalam setiap edisi Talmud sejak pertama kali dicetak oleh Daniel Bomberg pada tahun 1520-an. Komentarinya mengenai Tanakh — khususnya mengenai Chumash ("Lima Kitab Musa") — merupakan alat bantu penting bagi para pelajar dalam segala tingkatan. Tafsir yang kemudian juga menjadi dasar lebih dari 300 "supercommentaries" yang menganalisis pilihan bahasa dan kutipan Rashi, ditulis oleh sejumlah nama-nama besar dalam sastra rabbinik.[2]

Nama

Nama keluarga Rashi "Yitzhaki" diturunkan dari nama ayahnya, Yitzhak. Akronim namanya seringkali dikembangkan lebih indah sebagai "Rabban Shel YIsrael" yang artinya "rabbi Israel", or sebagai "Rabbenu SheYichyeh" ("Rabbi kami, biarlah dia hidup"). Ia dapat dirujuk dalam naskah-naskah Ibrani dan Aram sebagai

- (1) "Shlomo son of Rabbi Yitzhak,"

- (2) "Shlomo son of Yitzhak,"

- (3) "Shlomo Yitzhaki," dan lain-lain.[3]

Riwayat

Kelahiran dan Masa muda

Rashi adalah anak tunggal yang lahir di Troyes, Champagne, di bagian utara Perancis. Saudara laki-laki ibunya adalah Simon yang Tua, Rabbi di Mainz.[4] Simon was a disciple of Rabbeinu Gershom Meor HaGolah,[5] who died that same year. Dari pihak ayahnya, Rashi diklaim sebagai keturunan ke-33 dari Yochanan Hasandlar, yang merupakan keturunan ke-4 dari Gamaliel yang Tua, yang dikabarkan adalah keturunan Raja Daud. Dalam karya-karyanya yang berjumlah besar, Rashi sendiri tidak pernah mengklaim demikian. Sumber rabbinik awal utama mengenai silsilahnya, Responsum No. 29 oleh Solomon Luria, juga tidak membuat klaim semacam itu.[6][7]

Kematian dan makam

Rashi meninggal pada tanggal 13 Juli 1105 (29 Tammuz 4865) pada usia 65 tahun. Ia dimakamkan di Troyes, Perancis. Lokasi pekuburannya dicatat dalam Seder ha-Dorot (Seder Hadoros), tetapi lambat laun lokasi tepatnya dilupakan. Beberapa tahun berselang, seorang profesor University of Paris (Sorbonne) menemukan peta kuno yang menggambarkan lokasi makam, sekarang menjadi taman terbuka kota Troyes. Setelah penemuan ini, orang Yahudi Perancis mendirikan suatu monumen besar di tengah taman itu, berupa sebuah bola dunia besar berwarna hitam dan putih dengan huruf-huruf Ibrani yang menonjol, Shin (ש) (yaitu untuk "Shlomo", nama depan Rashi). Pada landasan granit monumen tersebut diukir Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki — Commentator and Guide (Komentator dan Pemandu).

Keturunan

Rashi tidak mempunyai putra, tetapi memiliki tiga anak perempuan, Miriam, Yocheved, dan Rachel, semuanya menikah dengan pakar-pakar Talmud. Ada legenda bahwa putri-putri Rashi mengenakan tefillin. Meskipun sejumlah perempuan Yahudi Ashkenazi pada abad pertengahan memakai tefillin, tidak ada bukti bahwa putri-putri Rashi memakainya.[8]

- Putri sulung Rashi, Yocheved, menikah dengan Meir ben Shmuel; empat putra mereka adalah:

- Shmuel (Rashbam) (lahir 1080),

- Yitzchak (Rivam) (lahir 1090),

- Jacob (Rabbeinu Tam) (lahir 1100), dan

- Shlomo the Grammarian (sang ahli gramatik), yang merupakan salah satu rabbi terkemuka dari Baalei Tosafos, yaitu otoritas rabbinik yang menulis kritik dan penjelasan pada Talmud yang muncul bersebelahan dengan komentari Rashi pada setiap halaman Talmud.

- putri Yocheved, Chanah, adalah seorang guru hukum dan kebiasaan yang berkenaan dengan perempuan.

- Putri tengah Rashi, Miriam, menikah dengan Judah ben Nathan, yang menyelesaikan komentari mengenai Talmud Makkot yang sedang dikerjakan Rashi ketika ia meninggal.[9] Putri mereka Alvina adalah seorang perempuan terpelajar yang kebiasaan-kebiasaannya menjadi dasar keputusan halakha di kemudian hari. Putra mereka Yom Tov ben Judah kemudian pindah ke Paris dan memimpin suatu yeshiva di sana, bersama saudara-saudara laki-lakinya Shimshon dan Eliezer.

- Putri bungsu Rashi, Rachel, menikah dengan (dan bercerai dari) Eliezer ben Shemiah.

Karya

Tafsir Rashi mengenai Tanakh

Tafsir Rashi mengenai Tanakh — dan terutama tafsirnya mengenai Chumash — merupakan pelengkap penting untuk studi Talmud apapun pada tingkatan apapun. Mengambil dari dalamnya sastra Midrashik, Talmudik dan Aggadik (termasuk literatur yang sekarang tidak ditemukan lagi), serta pengetahuannya akan tatabahasa, halakhah, dan bagaimana suatu hal itu terjadi, Rashi menjelaskan arti "sederhana" suatu naskah sehingga seorang anak berusia lima tahun yang cerdas dapat memahaminya.[10] Bersamaan dengan itu, tafsirnya meletakkan landasan beberapa penelaahan analisis dan mistikal hukum yang terdalam setelahnya. Para pakar berdebat mengapa Rashi memilih Midrash tertentu untuk menggambarkan suatu poin, atau mengapa ia menggunakan kata-kata dan frasa-frasa tertentu, bukan yang lain. Rabbi Shneur Zalman dari Liadi menulis bahwa "Tafsir Rashi mengenai Taurat merupakan ‘anggur Taurat’, yang membuka hati dan menyingkapkan kasih dan rasa takut yang esensial seseorang terhadap Allah."[11]

Tafsir Rashi mengenai Talmud

Rashi menulis tafsir atau komentari komprehensif pertama mengenai Talmud. Tafsir Rashi yang diambil dari pengetahuannya terhadap seluruh isi Talmud, berusaha untuk memberikan penjelasan lengkap mengenai kata-kata atau struktur logis setiap bacaan Talmudik. Berbeda dengan komentator-komentator lain, Rashi tidak melakukan parafrasa atau melompati bagian tertentu suatu naskah, melainkan menjabarkan frasa demi frasa. Seringkali ia memberikan tanda baca (punktuasi) untuk naskah yang tidak bertanda baca, misalnya menjelaskan "Apakah ini suatu pertanyaan"; "Ia mengatakan ini sambil terkejut", "Ia mengulangi hal ini untuk memberi persetujuan", dan sebagainya.

Peninggalan

Komentari Rashi mengenai Talmud terus menjadi dasar kunci penelitian dan interpretasi rabbinik kontemporer. Tanpa tafsir Rashi, Talmud dianggap "buku yang tertutup". Dengan komentarinya, setiap pelajar yang telah diperkenalkan oleh gurunya untuk mempelajari, akan dapat terus belajar sendiri, menguraikan bahasa dan maknanya dengan pertolongan Rashi.

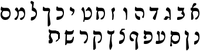

Aksara "Ibrani Rashi"

Jenis huruf semi-kursif yang dipakai untuk mencetak tafsir-tafsir Rashi, baik dalam Talmud dan Tanakh sering disebut tulisan "Ibrani Rashi" atau "Rashi script." Ini tidak berarti Rashi sendiri menggunakan aksara tersebut dalam naskahnya: jenis huruf ini berdasarkan tulisan tangan Yahudi Sefardim dari abad ke-15. Apa yang kemudian disebut "Rashi script" dipakai oleh tipografer Ibrani mula-mula seperti keluarga Soncino dan Daniel Bomberg, sebuah percetakan Kristen di Venice, dalam edisi naskah berkomentar (seperti Mikraot Gedolot dan Talmud, di mana komentar Rashi sangat menonjol) untuk membedakan tafsir rabbi dari naskah utamanya, yang dicetak dengan jenis huruf bujursangkar (square typeface).

Referensi

- ^ Ramban writes in the introduction to his commentary on Genesis: "I will place for the illumination of my face the lights of a pure candelabrum — the commentaries of Rabbi Shlomo (Rashi), crown of beauty and glory ... in Scripture, Mishnah, and Talmud, to him belongs the rights of the firstborn!" quoted at Biography of Ramban, The Jewish Theological Seminary

- ^ a b Miller, Chaim. Rashi's Method of Biblical Commentary. chabad.org

- ^ Cybernetics and Systems Volume 42, Issue 3, pages 180-197 29 Apr 2011 Available online: DOI:10.1080/01969722.2011.567893 article authors Yaakov HaCohen-Kerner, Nadav Schweitzer & Dror Mughaz title Automatically Identifying Citations in Hebrew-Aramaic Documents published Taylor & Francis "For example, the Pardes book written by Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki, known by the abbreviation Rashi, can be cited using the following patterns: (1) "Shlomo son of Rabbi Yitzhak," (2) "Shlomo son of Yitzhak," (3) "Shlomo Yitzhaki," (4) "In the name of Rashi who wrote in the Pardes"

- ^ "Index to Articles on Rabbinic Genealogy in Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy". Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy. Diakses tanggal 2008-06-11.

- ^ See Rashi's comments in Shabbat 85b.

- ^ Hurwitz, Simon (1938). The Responsa of Solomon Luria. New York, New York. hlm. 146–151.

- ^ Einsiedler, David (1992). "Can We Prove Descent from King David?". Avotaynu: the International Review of Jewish Genealogy. VIII (3(Fall)): 29. Diakses tanggal 2008-06-11.

- ^ Grossman, Avraham. Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe. Brandeis University Press, 2004.)

- ^ Makkot 19b: "Tubuh guru kami adalah murni, dan jiwanya berangkat dalam kemurnian, dan ia tidak menjelaskan lagi; sejak ini adalah bahasa muridnya Rabbi Yehudah ben Nathan."

- ^ Mordechai Menashe Laufer. "רבן של ישראל (Hebrew)".

- ^ Rashi's Method of Biblical Commentary

Pustaka tambahan

- Abecassis, Deborah Reconstructing Rashi's Commentary on Genesis from Citations in the Torah Commentaries in the Tosafot Dissertation 1999, Department of Jewish Studies, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec.

- Rashi The Jewish History Resource Center - Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Biography, the Legend, the Commentator and more rashi900.com

- Article on chabad.org

- Family Tree

- Rashi's Daughters: A Novel of Life, Love and Talmud in Medieval France

- In honor of the 900th anniversary of his passing

- Rashi; an exhibition of his works, from the treasures of the Jewish National and University Library

- Cantor, Norman F. (1969). Medieval History (edisi ke-2nd). Toronto, Canada: Macmillan. hlm. 396. ISBN 978-0-02-319070-4.

- Shulman, Yaacov Dovid (1993). Rashi: The Story of rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki. C.I.S. Publishers. ISBN 1-56062-215-6.

- Liber, Maurice (1905). Rashi. Translated from French by Adele Szold. Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 0-9766546-5-2.

- Wiesel, Elie (2009). Rashi. Translated from French by Catherine Temerson. Schocken Books. ISBN 0-8052-4254-6.

Sumber

- Teknik dan metodologi

- Full text resources and translation

- Textual Search

- Lookup Verses, rashiyomi.com

- Lookup Verses, tachash.org

- Complete Rashi script

Wikisource

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "perlu nama artikel ". Encyclopædia Britannica (edisi ke-11). Cambridge University Press. Teks "Rashi" akan diabaikan (bantuan)

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "perlu nama artikel ". Encyclopædia Britannica (edisi ke-11). Cambridge University Press. Teks "Rashi" akan diabaikan (bantuan) "Rashi". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

"Rashi". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

Pranala luar

- Artikel Wikipedia yang memuat kutipan dari Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911 dengan parameter tanpa nama

- Articles with deprecated authority control identifiers

- Halaman yang menggunakan pengawasan otoritas dengan parameter berbeda dari Wikidata

- Kelahiran 1040

- Kematian 1105

- Tokoh Yahudi

- Rishonim

- Bible commentators

- Worms, Germany