Teori Keluar dari India: Perbedaan antara revisi

←Membuat halaman berisi '{{Short description|Pandangan bahwa bangsa India-Arya adalah bangsa pribumi India}} {{pp|small=yes}} {{semiprotected|small=yes}} {{Indo-European topics}} '''Pribumi Aryanisme''', yang juga dikenal dengan sebutan '''Teori Pribumi Arya''' dan '''Teori Keluar dari India''', adalah keyakinan{{sfn|Bryant|2001|p=4}} bahwa bangsa Arya adalah bangsa pribumi Anak Benua India,{{sfn|Trautmann|2005|p=xxx}} dan bahwasanya Rumpun bahasa...' Tag: halaman dengan galat kutipan pranala ke halaman disambiguasi |

(Tidak ada perbedaan)

|

Revisi per 5 Januari 2023 08.18

| Artikel ini adalah bagian dari seri: |

| Topik Indo-Eropa |

|---|

|

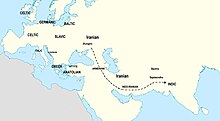

Pribumi Aryanisme, yang juga dikenal dengan sebutan Teori Pribumi Arya dan Teori Keluar dari India, adalah keyakinan[1] bahwa bangsa Arya adalah bangsa pribumi Anak Benua India,[2] dan bahwasanya bahasa-bahasa rumpun India-Eropa berpancaran dari suatu tempat asal di India ke tempat-tempatnya dituturkan dewasa ini.[2] Keyakinan ini merupakan suatu pandangan yang bersifat "agamawi-nasionalistis" terhadap sejarah bangsa India,[3][4] dan dikemukakan sebagai alternatif bagi model migrasi yang sudah lazim diketahui,[5] yang mendapuk stepa Pontus-Kaspia sebagai tempat asal bahasa-bahasa rumpun India-Eropa.[6][7][8][note 1]

Sembari mendalami pandangan-pandangan India tradisonal[3] yang berasaskan kronologi Purana, para indigenis mengusulkan pertanggalan yang lebih tua daripada pertanggalan yang sudah berterima umum untuk zaman Weda, serta mengemukakan pandangan bahwa peradaban Lembah Sungai Sindu adalah peradaban zaman Weda. Menurut pandangan ini, "peradaban bangsa India haruslah dipandang sebagai suatu tradisi tak terputus yang dapat dirunut balik sampai kepada kurun waktu terawal dari tradisi Sindu-Saraswati (7000 atau 8000 tahun Pramasehi)."[9]

Sebagian besar pendukung Teori Pribumi Arya berasal dari kalangan khusus sarjana India yang menekuni bidang kajian agama Hindu, sejarah, maupun arkeologi India,[10][11][12][13][5] dan memainkan peranan penting di kancah politik Hindutwa.[14][15][3][web 1][web 2] Teori ini tidak lazim dijumpai apalagi mendapatkan dukungan di kalangan sarjana arus utama.[note 2]

Latar belakang sejarah

Pandangan standar mengenai asal-usul bangsa India-Arya adalah teori migrasi bangsa India-Arya, yang mengatakan bahwa bangsa India-Arya masuk ke kawasan barat laut India sekitar tahun 1500 Pramasehi.[6] Kronologi Purana, yakni lini masa peristiwa-peristiwa sepanjang perjalanan sejarah bangsa India Kuno, sebagaimana diriwayatkan di dalam Mahabarata, Ramayana, dan pustaka-pustaka Purana, memunculkan bayangan akan suatu kronologi yang jauh lebih tua bagi peradaban zaman Weda. Menurut alur pemahaman tersebut, susastra-susatra Weda diterima ribuan tahun silam, dan masa pemerintahan Vaivasvata Manu, yakni Manu untuk kalpa berjalan, leluhur umat manusia, diperkirakan bermula pada tahun 7350 Pramasehi.[16] Perang Kurusetra, latar susastra Begawat Gita, yang mungkin saja meriwayatkan peristiwa-peristiwa yang benar-benar terjadi sekitar tahun 1000 Pramasehi di pusat Aryawarta,[17][18] dipertanggal sekitar tahun 3100 Pramasehi di dalam kronologi ini.

Para indigenis, sembari mendalami pandangan-pandangan India tradisional terkait sejarah dan agama,[3] mengemukakan pandangan bahwa bangsa Arya adalah bangsa pribumi India, menantang pandangan standar.[6] Pada dasawarsa 1980-an dan 1990-an, pendirian pribumi tersebut sudah mengemuka di pentas perdebatan umum.[19]

[note 3] The Bharata War is dated at 3139–38 BCE, the start of the kali Yuga.[note 4]

Indigenous Aryans scenarios

Michael Witzel identifies three major types of "Indigenous Aryans" scenarios:[22]

1. A "mild" version that insists on the indigeneity of the Rigvedic Aryans to the North-Western region of the Indian subcontinent in the tradition of Aurobindo and Dayananda;[note 5]

2. The "out of India" school that posits India as the Proto-Indo-European homeland, originally proposed in the 18th century, revived by the Hindutva sympathiser[24] Koenraad Elst (1999), and further popularised within Hindu nationalism[25] by Shrikant Talageri (2000);[23][note 6]

3. The position that all the world's languages and civilisations derive from India, represented e.g. by David Frawley.

Kazanas adds a fourth scenario:

4.The Aryans entered the Indus Valley before 4500 BCE and got integrated with the Harappans, or might have been the Harappans.[27]

Aurobindo's Aryan world-view

For Aurobindo, an "Aryan" was not a member of a particular race, but a person who "accepted a particular type of self-culture, of inward and outward practice, of ideality, of aspiration."[28] Aurobindo wanted to revive India's strength by reviving Aryan traditions of strength and character.[29] He denied the historicity of a racial division in India between "Aryan invaders" and a native dark-skinned population. Nevertheless, he did accept two kinds of culture in ancient India, namely the Aryan culture of northern and central India and Afghanistan, and the un-Aryan culture of the east, south and west. Thus, he accepted the cultural aspects of the division suggested by European historians.[30]

Out of India model

The "Out of India theory" (OIT), also known as the "Indian Urheimat theory," is the proposition that the Indo-European language family originated in Northern India and spread to the remainder of the Indo-European region through a series of migrations.[web 5] It implies that the people of the Harappan civilisation were linguistically Indo-Aryans.[31]

Theoretical overview

Koenraad Elst, in his Update in the Aryan Invasion Debate, investigates "the developing arguments concerning the Aryan Invasion Theory".[32] Elst notes:[33]

Personally, I don't think that either theory, of Aryan invasion and of Aryan indigenousness, can claim to have been proven by prevalent standards of proof; even though one of the contenders is getting closer. Indeed, while I have enjoyed pointing out the flaws in the AIT statements of the politicized Indian academic establishment and its American amplifiers, I cannot rule out the possibility that the theory which they are defending may still have its merits.

Edwin Bryant also notes that Elst's model is a "theoretical exercise:"[34]

...a purely theoretical linguistic exercise […] as an experiment to determine whether India can definitively be excluded as a possible homeland. If it cannot, then this further problematizes the possibility of a homeland ever being established anywhere on linguistic grounds.

And in Indo-Aryan Controversy Bryant notes:[35]

Elst, perhaps more in a mood of devil's advocacy, toys with the evidence to show how it can be reconfigured, and to claim that no linguistic evidence has yet been produced to exclude India as a homeland that cannot be reconfigured to promote it as such.

"The emerging alternative"

Koenraad Elst summarises "the emerging alternative to the Aryan Invasion Theory" as follows.[36]

During the 6th millennium BCE Proto-Indo-Europeans lived in the Punjab region of northern India. As the result of demographic expansion, they spread into Bactria as the Kambojas. The Paradas moved further and inhabited the Caspian coast and much of central Asia while the Cinas moved northwards and inhabited the Tarim Basin in northwestern China, forming the Tocharian group of I-E speakers. These groups were Proto-Anatolian and inhabited that region by 2000 BCE. These people took the oldest form of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language with them and, while interacting with people of the Anatolian and Balkan region, transformed it into a separate dialect. While inhabiting central Asia they discovered the uses of the horse, which they later sent back to the Urheimat.[36] Later on during their history, they went on to occupy western Europe and thus spread the Indo-European languages to that region.[36]

During the 4th millennium BCE, civilisation in India started evolving into what became the urban Indus Valley civilization. During this time, the PIE languages evolved to Proto-Indo-Iranian.[36] Some time during this period, the Indo-Iranians began to separate as the result of internal rivalry and conflict, with the Iranians expanding westwards towards Mesopotamia and Persia, these possibly were the Pahlavas. They also expanded into parts of central Asia. By the end of this migration, India was left with the Proto-Indo-Aryans. At the end of the Mature Harappan period, the Sarasvati river began drying up and the remainder of the Indo-Aryans split into separate groups. Some travelled westwards and established themselves as rulers of the Hurrian Mitanni kingdom by around 1500 BCE (see Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni). Others travelled eastwards and inhabited the Gangetic basin while others travelled southwards and interacted with the Dravidian people.[36]

David Frawley

In books such as The Myth of the Aryan Invasion of India and In Search of the Cradle of Civilization (1995), Frawley criticises the 19th century racial interpretations of Indian prehistory, such as the theory of conflict between invading Caucasoid Aryans and Dravidians.[37] In the latter book, Frawley, Georg Feuerstein, and Subhash Kak reject the Aryan Invasion theory and support Out of India.

Bryant commented that Frawley's historical work is more successful as a popular work, where its impact "is by no means insignificant", rather than as an academic study,[38] and that Frawley "is committed to channelling a symbolic spiritual paradigm through a critical empirico rational one".[39]

Pseudo-historian[40] Graham Hancock (2002) quotes Frawley's historical work extensively for the proposal of highly evolved ancient civilisations prior to the end of the last glacial period. including in India.[41] Kreisburg refers to Frawley's "The Vedic Literature and Its Many Secrets".[42]

Significance for colonial rule and Hindu politics

The Aryan Invasion theory plays an important role in Hindu nationalism, which favors Indigenous Aryanism.[43] It has to be understood against the background of colonialism and the subsequent task of nation-building in India.

Colonial India

Curiosity and the colonial requirements of knowledge about their subject people led the officials of the East India Company to explore the history and culture of India in the late 18th century.[44] When similarities between Sanskrit, Greek and Latin were discovered by William Jones, a suggestion of "monogenesis" (single origin) was formulated for these languages as well as their speakers. In the latter part of the 19th century, it was thought that language, culture and race were inter-related, and the notion of biological race came to the forefront[45] The presumed "Aryan race" which originated the Indo-European languages was prominent among such races, and was deduced to be further subdivided into "European Aryans" and "Asian Aryans," each with their own homelands.[46]

Max Mueller, who translated the Rigveda during 1849–1874, postulated an original homeland for all Aryans in central Asia, from which a northern branch migrated to Europe and a southern branch to India and Iran. The Aryans were presumed to be fair-complexioned Indo-European speakers who conquered the dark-skinned dasas of India. The upper castes, particularly the Brahmins, were thought to be of Aryan descent whereas the lower castes and Dalits ("untouchables") were thought to be the descendants of dasas.[47]

The Aryan theory served politically to suggest a common ancestry and dignity between the Indians and the British. Keshab Chunder Sen spoke of British rule in India as a "reunion of parted cousins." Indian nationalist Bal Gangadhar Tilak endorsed the antiquity of Rigveda, dating it to 4500 BCE. He placed the homeland of the Aryans somewhere close to the North Pole. From there, Aryans were believed to have migrated south in the post-glacial age, branching into a European branch that relapsed into barbarism and an Indian branch that retained the original, superior civilisation.[48]

However, Christian missionaries such as John Muir and John Wilson drew attention to the plight of lower castes, who they said were oppressed by the upper castes since the Aryan invasions. Jyotiba Phule argued that the dasas and sudras were indigenous people and the rightful inheritors of the land, whereas Brahmins were Aryan and alien.[49]

Hindu revivalism and nationalism

In contrast to the mainstream views, the Hindu revivalist movements denied an external origin to Aryans. Dayananda Saraswati, the founder of the Arya Samaj (Society of Aryans), held that Vedas were the source of all knowledge and were revealed to the Aryans. The first man (an Aryan) was created in Tibet and, after living there for some time, the Aryans came down and inhabited India, which was previously empty.[50]

The Theosophical Society held that the Aryans were indigenous to India, but that they were also the progenitors of the European civilisation. The Society saw a dichotomy between the spiritualism of India and the materialism of Europe.[51]

According to Romila Thapar, the Hindu nationalists, led by Savarkar and Golwalkar, eager to construct a Hindu identity for the nation, held that the original Hindus were the Aryans and that they were indigenous to India. There was no Aryan invasion and no conflict among the people of India. The Aryans spoke Sanskrit and spread the Aryan civilization from India to the west.[51]

Witzel traces the "indigenous Aryan" idea to the writings of Savarkar and Golwalkar. Golwalkar (1939) denied any immigration of "Aryans" to the subcontinent, stressing that all Hindus have always been "children of the soil", a notion which according to Witzel is reminiscent of the blood and soil of contemporary fascism. Since these ideas emerged on the brink of the internationalist and socially oriented Nehru-Gandhi government, they lay dormant for several decades, and only rose to prominence in the 1980s.[52]

Bergunder likewise identifies Golwalkar as the originator of the "Indigenous Aryans" notion, and Goel's Voice of India as the instrument of its rise to notability:[53]

The Aryan migration theory at first played no particular argumentative role in Hindu nationalism. […] This impression of indifference changed, however, with Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar (1906–1973), who from 1940 until his death was leader of the extremist paramilitary organization the Rashtriya Svayamsevak Sangh (RSS). […] In contrast to many other of their openly offensive teachings, the Hindu nationalists did not seek to keep the question of the Aryan migration out of public discourses or to modify it; rather, efforts were made to help the theory of the indigenousness of the Hindus achieve public recognition. For this the initiative of the publisher Sita Ram Goel (b. 1921) was decisive. Goel may be considered one of the most radical, but at the same time also one of the most intellectual, of the Hindu nationalist ideologues. […] Since 1981 Goel has run a publishing house named ‘Voice of India' that is one of the few which publishes Hindu nationalist literature in English which at the same time makes a 'scientific' claim. Although no official connections exist, the books of 'Voice of India' — which are of outstanding typographical quality and are sold at a subsidized price — are widespread among the ranks of the leaders of the Sangh Parivar. […] The increasing political influence of Hindu nationalism in the 1990s resulted in attempts to revise the Aryan migration theory also becoming known to the academic public.

Present-day political significance

Lars Martin Fosse notes the political significance of "Indigenous Aryanism".[43] He notes that "Indigenous Aryanism" has been adopted by Hindu nationalists as a part of their ideology, which makes it a political matter in addition to a scholarly problem.[43] The proponents of Indigenous Aryanism necessarily engage in "moral disqualification" of Western Indology, which is a recurrent theme in much of the indigenist literature. The same rhetoric is being used in indigenist literature and the Hindu nationalist publications like the Organiser.[54]

According to Abhijith Ravinutala, the indigenist position is essential for Hindutva exclusive claims on India:[15]

The BJP considers Indo-Aryans fundamental to the party's conception of Hindutva, or "Hindu-ness": India is a nation of and for Hindus only. Only those who consider India their holy land should remain in the nation. From the BJP's point of view, the Indo-Aryan peoples were indigenous to India, and therefore were the first 'true Hindus'. Accordingly, an essential part of 'Indian' identity in this point of view is being indigenous to the land.

Repercussions of the disagreements about Aryan origins have reached Californian courts with the Californian Hindu textbook case, where according to the Times of India[web 6] historian and president of the Indian History Congress, Dwijendra Narayan Jha in a "crucial affidavit" to the Superior Court of California:[web 6]

...[g]iving a hint of the Aryan origin debate in India, ... asked the court not to fall for the 'indigenous Aryan' claim since it has led to 'demonisation of Muslims and Christians as foreigners and to the near denial of the contributions of non-Hindus to Indian culture'.

According to Thapar, Modi's government and the BJP have "peddled myths and stereotypes," such as the insistence on "a single uniform culture of the Aryans, ancestral to the Hindu, as having prevailed in the subcontinent, subsuming all others," despite the scholarly evidence for migrations into India, which is "anathema to the Hindutva construction of early history."[web 7]

Rejection by mainstream scholarship

The Indigenous Aryans theory has no relevance, let alone support, in mainstream scholarship.[note 2] According to Michael Witzel, the "indigenous Aryans" position is not scholarship in the usual sense, but an "apologetic, ultimately religious undertaking":[3]

The "revisionist project" certainly is not guided by the principles of critical theory but takes, time and again, recourse to pre-enlightenment beliefs in the authority of traditional religious texts such as the Purāṇas. In the end, it belongs, as has been pointed out earlier, to a different 'discourse' than that of historical and critical scholarship. In other words, it continues the writing of religious literature, under a contemporary, outwardly 'scientific' guise ... The revisionist and autochthonous project, then, should not be regarded as scholarly in the usual post-enlightenment sense of the word, but as an apologetic, ultimately religious undertaking aiming at proving the "truth" of traditional texts and beliefs. Worse, it is, in many cases, not even scholastic scholarship at all but a political undertaking aiming at "rewriting" history out of national pride or for the purpose of "nation building".

In her review of Bryant's The Indo-Aryan Controversy, which includes chapters by Elst and other "indigenists", Stephanie Jamison comments:[4]

... the parallels between the Intelligent Design issue and the Indo-Aryan "controversy" are distressingly close. The Indo-Aryan controversy is a manufactured one with a non-scholarly agenda, and the tactics of its manufacturers are very close to those of the ID proponents mentioned above. However unwittingly and however high their aims, the two editors have sought to put a gloss of intellectual legitimacy, with a sense that real scientific questions are being debated, on what is essentially a religio-nationalistic attack on a scholarly consensus.

Sudeshna Guha, in her review of The Indo-Aryan Controversy, notes that the book has serious methodological shortcomings, by not asking the question what exactly constitutes historical evidence.[56] This makes the "fair and adequate representation of the differences of opinion" problematic, since it neglects "the extent to which unscholarly opportunism has motivated the rebirth of this genre of 'scholarship'".[56] Guha:[56]

Bryant's call for accepting "the valid problems that are pointed out on both sides" (p. 500), holds intellectual value only if distinctions are strictly maintained between research that promotes scholarship, and that which does not. Bryant and Patton gloss over the relevance of such distinctions for sustaining the academic nature of the Indo-Aryan debate, although the importance of distinguishing the scholarly from the unscholarly is rather well enunciated through the essays of Michael Witzel and Lars Martin Fosse.

According to Bryant,[57] OIT proponents tend to be linguistic dilettantes who either ignore the linguistic evidence completely, dismiss it as highly speculative and inconclusive,[note 7] or attempt to tackle it with hopelessly inadequate qualifications; this attitude and neglect significantly minimises the value of most OIT publications.[59][60][note 8]

Fosse notes crucial theoretical and methodological shortcomings in the indigenist literature.[62] Analysing the works of Sethna, Bhagwan Singh, Navaratna and Talageri, he notes that they mostly quote English literature, which is not fully explored, and omitting German and French Indology. It makes their works in various degrees underinformed, resulting in a critique that is "largely neglected by Western scholars because it is regarded as incompetent".[63]

According to Erdosy, the indigenist position is part of a "lunatic fringe" against the mainstream migrationist model. [64][note 9]

See also

Indo-Aryans

Politics

Indigenists

Books

- The Arctic Home in the Vedas (1903)

- In Search of the Cradle of Civilization

- Aryan Invasion of India: The Myth and the Truth (1993)

- Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate (1999)

- The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis (2000)

Other

Notes

- ^ Entry of the Indo-Aryans:

* (Lowe 2015, hlm. 1–2): "... the eastward migration of the Indo-Aryan tribes from the mountains of what is today northern Afghanistan across the Punjab into north India."

* (Dyson 2018, hlm. 14–15): "Although the collapse of the Indus valley civilization is no longer believed to have been due to an ‘Aryan invasion’ it is widely thought that, at roughly the same time, or perhaps a few centuries later, new Indo-Aryan-speaking people and influences began to enter the subcontinent from the north-west. Detailed evidence is lacking. Nevertheless, a predecessor of the language that would eventually be called Sanskrit was probably introduced into the north-west sometime between 3,900 and 3,000 years ago. This language was related to one then spoken in eastern Iran; and both of these languages belonged to the Indo-European language family."

* (Pinkney 2014, hlm. 38): "According to Asko Parpola, the Proto-Indo-Aryan civilization was influenced by two external waves of migrations. The first group originated from the southern Urals (c. 2100 BCE) and mixed with the peoples of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC); this group then proceeded to South Asia, arriving around 1900 BCE. The second wave arrived in northern South Asia around 1750 BCE and mixed with the formerly arrived group, producing the Mitanni Aryans (c. 1500 BCE), a precursor to the peoples of the Ṛgveda." - ^ a b No support in mainstream scholarship:

- (Mallory 2013): "The speakers at this symposium can generally be seen to support one of the following three ‘solutions’ to the Indo-European homeland problem: 1. The Anatolian Neolithic model [...] 2. The Near Eastern model [...] 3. The Pontic-Caspian model."

- Romila Thapar (2006): "there is no scholar at this time seriously arguing for the indigenous origin of Aryans".[55]

- Wendy Doniger (2017): "The opposing argument, that speakers of Indo-European languages were indigenous to the Indian subcontinent, is not supported by any reliable scholarship. It is now championed primarily by Hindu nationalists, whose religious sentiments have led them to regard the theory of Aryan migration with some asperity."[web 1]

- (Truschke 2020): "As Tony Joseph has pointed out, the Out of India theory lacks support from even “a single, peer-reviewed scientific paper” and is best considered nothing “more than a kind of clever and angry retort.”"

- Girish Shahane (September 14, 2019), in response to Narasimhan et al. (2019): "Hindutva activists, however, have kept the Aryan Invasion Theory alive, because it offers them the perfect strawman, 'an intentionally misrepresented proposition that is set up because it is easier to defeat than an opponent's real argument' [...] The Out of India hypothesis is a desperate attempt to reconcile linguistic, archaeological and genetic evidence with Hindutva sentiment and nationalistic pride, but it cannot reverse time's arrow [...] The evidence keeps crushing Hindutva ideas of history."[web 2]

- Koenraad Elst (May 10, 2016): "Of course it is a fringe theory, at least internationally, where the Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT) is still the official paradigm. In India, though, it has the support of most archaeologists, who fail to find a trace of this Aryan influx and instead find cultural continuity."[5]

- ^ Witzel calls these "absurd dates", and refers to Elst 1999, Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate, p.97 for more of them.[20]

Elst: "It is not only the Vedic age which is moved a number of centuries deeper into the past, when comparing the astronomical indications with the conventional chronology. Even the Gupta age (and implicitly the earlier ages of the Buddha, the Mauryas etc.) could be affected. Indeed, the famous playwright and poet Kalidasa, supposed to have worked at the Gupta court in about 400 AD, wrote that the monsoon rains started at the start of the sidereal month of Ashadha; this timing of the monsoon was accurate in the last centuries BCE. This implicit astronomy-based chronology of Kalidasa, about 5 centuries higher than the conventional one, tallies well with the traditional high chronology of the Buddha, whom Chinese Buddhist tradition dates to c. 1100 BC, and the implicit Puranic chronology even to c. 1700 BC.[web 3]

Elst 1999 2.3 note 17: "The argument for a higher chronology (by about 6 centuries) for the Guptas as well as for the Buddha has been elaborated by K.D. Sethna in Ancient India in New Light, Aditya Prakashan, Delhi 1989. The established chronology starts from the uncertain assumption that the Sandrokottos/ Chandragupta whom Megasthenes met was the Maurya rather than the Gupta king of that name. This hypothetical synchronism is known as the sheet-anchor of Indian chronology.[web 3] - ^ Elst: "In August 1995, a gathering of 43 historians and archaeologists from South-Indian universities (at the initiative of Prof. K.M. Rao, Dr. N. Mahalingam and Dr. S.D. Kulkarni) passed a resolution fixing the date of the Bharata war at 3139–38 BC and declaring this date to be the true sheet anchor of Indian chronology."[web 3]

The Indic Studies Foundation reports of another meeting in 2003: "Scholars from across the world came together, for the first time, in an attempt to establish the 'Date of Kurukshetra War based on astronomical data.'"[web 4] - ^ Witzel mentions:[22]

- Aurobindo (no specific source)

- Waradpande, N.R., "Fact and fictions about the Aryans." In: Deo and Kamath 1993, 14-19

- Waradpande, N.R., "The Aryan Invasion, a Myth." Nagpur: Baba Saheb Apte Smarak Samiti 1989

- S. Kak 1994a, "On the classification of Indic languages." Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 75, 1994a, 185-195.

- Elst 1999, "Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate." Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. p.119

- Talageri 2000, "Rigveda. A Historical Analysis." New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, p.406 sqq,[23]

- Lal 1997, "The Earliest Civilization of South Asia (Rise, Maturity and Decline)." New Delhi: Aryan Books International, p.281 sqq.

- ^ In any "Indigenous Aryan" scenario, speakers of Indo-European languages must have left India at some point prior to the 10th century BCE, when first mention of Iranian peoples is made in Assyrian records, but likely before the 16th century BCE, before the emergence of the Yaz culture which is often identified as a Proto-Iranian culture. (See, e.g., Roman Ghirshman, L'Iran et la migration des Indo-aryens et des Iraniens).[26]

- ^ E.g. Chakrabarti 1995 and Rajaram 1995, as cited in Bryant 2001.[58]

- ^ Witzel: "linguistic data have generally been neglected by advocates of the autochthonous theory. The only exception so far is a thin book by the Indian linguist S. S. Misra (1992) which bristles with inaccuracies and mistakes (see below) and some, though incomplete discussion by Elst (1999)."[61]

- ^ Erdosy: "Assertions of the indigenous origin of Indo-Aryan languages and an insistence on a long chronology for Vedic and even Epic literature are only a few of the most prominent tenets of this emerging lunatic fringe."[64]

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "chariot" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

<ref> dengan nama "Vedas" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.References

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 4.

- ^ a b Trautmann 2005, hlm. xxx.

- ^ a b c d e Witzel 2001, hlm. 95.

- ^ a b Jamison 2006.

- ^ a b c Koenraad Elst (May 10, 2016), Koenraad Elst: "I am not aware of any governmental interest in correcting distorted history", Swarajya Magazine

- ^ a b c Trautmann 2005, hlm. xiii.

- ^ Anthony 2007.

- ^ Parpola 2015.

- ^ Kak 2001b.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 292-293.

- ^ Bryant & Patton 2005.

- ^ Singh 2008, hlm. 186.

- ^ Bresnan 2017, hlm. 8.

- ^ Fosse 2005, hlm. 435-437.

- ^ a b Ravinutala 2013, hlm. 6.

- ^ Rocher 1986, hlm. 122.

- ^ Witzel 1995.

- ^ Singh 2009, hlm. 19.

- ^ Trautmann 2005, hlm. xiii-xv.

- ^ Witzel 2001, hlm. 88 note 220.

- ^ Kazanas (2013), The Collapse of the AIT

- ^ a b Witzel 2001, hlm. 28.

- ^ a b Talageri 2000.

- ^ Hansen 1999, hlm. 262.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 344.

- ^ Roman Ghirshman, L'Iran et la migration des Indo-aryens et des Iraniens(Leiden 1977). Cited by Carl .C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, Archaeology and language: The case of the Bronze Age Indo-Iranians, in Laurie L. Patton & Edwin Bryant, Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History (Routledge 2005), p. 162.

- ^ Kazanas 2002.

- ^ Heehs 2008, hlm. 255-256.

- ^ Boehmer 2010, hlm. 108.

- ^ Varma 1990, hlm. 79.

- ^ Bryant 2001.

- ^ Elst 1999.

- ^ Elst 1999, hlm. $6.2.3.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 147.

- ^ Bryant & Patton 2005, hlm. 468.

- ^ a b c d e Elst 1999, hlm. $6.3.

- ^ Arvidsson 2006, hlm. 298.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 291.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 347.

- ^ Fritze 2009, hlm. 214–218.

- ^ Hancock 2002, hlm. 137, 147–8, 157, 158, 166–7, 181, 182.

- ^ Kreisburg 2012, hlm. 22–38.

- ^ a b c Fosse 2005, hlm. 435.

- ^ Thapar 1996, hlm. 3.

- ^ Thapar 1996, hlm. 4.

- ^ Thapar 1996, hlm. 5.

- ^ Thapar 1996, hlm. 6.

- ^ Thapar 1996, hlm. 8.

- ^ Thapar 1996, hlm. 7.

- ^ Jaffrelot 1996, hlm. 16.

- ^ a b Thapar 1996, hlm. 9.

- ^ Witzel 2006, hlm. 204–205.

- ^ Bergunder 2004.

- ^ Fosse 2005, hlm. 437.

- ^ Thapar 2006.

- ^ a b c Guha 2007, hlm. 341.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 75.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 74.

- ^ Bryant 2001, hlm. 74–107.

- ^ Bryant 1996.

- ^ Witzel 2001, hlm. 32.

- ^ Fosse 2005.

- ^ Fosse 2005, hlm. 438.

- ^ a b Erdosy 2012, hlm. x.

- ^ Parpola 2020.

Sources

- Printed sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press.

- Anthony, David W. (2019). "Ancient DNA, Mating Networks, and the Anatolian Split". Dispersals and Diversification. Leiden: Brill. hlm. 21–53. doi:10.1163/9789004416192_003. ISBN 9789004416192.

- Anthony, David (2021), Daniels, Megan, ed., "Homo Migrans: Modeling Mobility and Migration in HUman HIstory", Migration, ancient DNA, and Bronze Age pastoralists from the Eurasian steppes, SUNY Press

- Arvidsson, Stefan (2006). Aryan Idols: Indo-European Mythology as Ideology and Science. University of Chicago Press.

- Basu (2003), "Ethnic India: A Genomic View, With Special Reference to Peopling and Structure", Genome Research, 13 (10): 2277–2290, doi:10.1101/gr.1413403, PMC 403703

, PMID 14525929

, PMID 14525929 - Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2994-1.

- Bergunder, Michael (2004). "Contested Past: Anti-Brahmanical and Hindu nationalist reconstructions of Indian prehistory" (PDF). Historiographia Linguistica. 31 (1): 59–104. doi:10.1075/hl.31.1.05ber.

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew, ed. (1997). Archaeology and Language. I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations. London: Routledge.

- Boehmer, Elleke (2010). Empire, the National, and the Postcolonial, 1890–1920: Resistance in Interaction. Oxford University Press.

- Bresnan, Patrick S. (2017), Awakening: An Introduction to the History of Eastern Thought (edisi ke-6th), Routledge

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2007). Greater Magadha: Studies in the Culture of Early India. BRILL.

- Bryant, Edwin F. (1996). Linguistic Substrata and the Indigenous Aryan Debate.

- Bryant, Edwin (1997). The indigenous Aryan debate (Tesis). Columbia University.

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513777-9.

- Bryant, Edwin F.; Patton, Laurie L. (2005). The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Routledge.

- Danino, Michel (2010). The Lost River: On the Trail of the Sarasvati. Penguin Books India.

- Darian, Steven G. (2001). "5. Ganga and Sarasvati: The Transformation of Myth". The Ganges in Myth and History. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1757-9.

- Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica [b] (n.d.). "Other sources: the process of "Sanskritization"". Encyclopædia Britannica. The history of Hinduism " Sources of Hinduism " Non-Indo-European sources " The process of "Sanskritization".

- Elst, Koenraad (1999). Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-86471-77-4. Diarsipkan dari versi asli tanggal 2013-08-07. Diakses tanggal 2006-12-21.

- Elst, Koenraad (2005). "Linguistic Aspects of the Aryan Non-Invasion Theory". Dalam Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L. The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Routledge.

- Erdosy, George (1995). "The prelude to Urbanization: Ethnicity and the Rise of Late Vedic Chiefdoms". Dalam Allchin, F. R. The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press.

- Erdosy (2012). The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity. ISBN 9783110816433.

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press.

- Flood, Gavin (2013) [1996], An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press

- Fosse, Lars Martin (2005). "Aryan Past and Post-colonial Present: The Polemics and Politics of Indigenous Aryanism". Dalam Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L. The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Routledge.

- Friese, Kai (2019). "The Complications of Genetics". Dalam R. Thapar; M. Witzel; J. Menon; K. Friese; R. Khan. Which of Us Are Aryans?. ALEPH.

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2009). Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-religions. London: Reaktion Books.

- Giosan; et al. (2012). "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization". PNAS. 109 (26): E1688–E1694. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E1688G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109

. PMC 3387054

. PMC 3387054  . PMID 22645375.

. PMID 22645375. - Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (1998). Hitler's Priestess: Savitri Devi, the Hindu-Aryan Myth, and Neo-Nazism. New York University. ISBN 0-8147-3111-2.

- Guha, Sudeshna (2007). "Reviewed Work: The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History by Edwin F. Bryant, Laurie Patton". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series. 17 (3): 340–343. doi:10.1017/S135618630700733X.

- Hancock, Graham (2002). Underworld: Flooded Kingdoms of the Ice Age. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-7181-4400-7.

- Hansen, Thomas Blom (1999). The Saffron Wave: Democracy and Hindu Nationalism in Modern India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2305-5.

- Heehs, Peter (2008). The Lives of Sri Aurobindo. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14098-0.

- Hewson, John (1997). Tense and Aspect in Indo-European Languages. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Hickey, Raymond (2010). "Contact and Language Shift". Dalam Hickey, Raymond. The Handbook of Language Contact. John Wiley & Sons.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (1996). The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-301-1.

- Jamison, Stephanie W. (2006). "The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History (Book Review)" (PDF). Journal of Indo-European Studies. 34: 255–261.

- Jha, D. N. (1998). "Against Communalising History". Social Scientist. 26 (9/10): 52–62. doi:10.2307/3517941. JSTOR 3517941.

- Kak, Subhash (1987). "On the Chronology of Ancient India" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science (22): 222–234. Diarsipkan dari versi asli (PDF) tanggal 2015-01-22. Diakses tanggal 29 January 2015.

- Kak, Subhash (1996). "Knowledge of Planets in the Third Millennium BC" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 37: 709–715. Bibcode:1996QJRAS..37..709K.

- Kak, Subhash (2001). The Wishing Tree: Presence and Promise of India. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 0-595-49094-8.

- Kak, Subhash (2001b), "On the Chronological Framework for Indian Culture" (PDF), Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research

- Kak, Subhash (2015). "The Mahabharata and the Sindhu-Sarasvati Tradition" (PDF). Sanskrit Magazine. Diakses tanggal 22 January 2015.

- Kazanas, Nicholas (2001). "A new date for the Rgveda" (PDF). Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research (special issue).

- Kazanas, N. (2002). "Indigenous Indo-Aryans and the Rigveda" (PDF). Journal of Indo-European Studies. 30: 275–334. Diakses tanggal 30 December 2009.

- Kazanas, N. (2003). "Final Reply" (PDF). Journal of Indo-European Studies. 31: 187–240. Diakses tanggal 30 December 2009.

- Kennedy, Kenneth A. R. (2000). God-apes and Fossil Men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472110131.

- Kennedy, Kenneth A.R. (2012), "Have Aryans been identified in the prehistorical skeletal record from South Asia? Biological anthropology and cocnepts of ancient races", dalam Erdosy, George, The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity, Walter de Gruyter

- Khan, Razib (2019), "Genetic origins of Indo-Aryans", dalam R. Thapar; M. Witzel; J. Menon; K. Friese; R. Khan, Which of Us Are Aryans?, ALEPH

- Kreisburg, Glenn (2012). Mysteries of the Ancient Past: A Graham Hancock Reader. Bear and Company. ISBN 978-1-59143-155-8.

- Kumar, Senthil (2012). Read Indussian: The Archaic Tamil from c. 7000 BCE. Amarabharathi Publications & Booksellers.

- Kurien, Prema A (2007). A place at the multicultural table the development of an American Hinduism (dalam bahasa Inggris). Rutgers University Press. hlm. 255. ISBN 9780813540559. OCLC 703221465.

- Kuz'mina, Elena Efimovna (1994). Откуда пришли индоарии? [Whence came the Indo-Aryans?] (dalam bahasa Rusia). Moscow: Российская академия наук (Russian Academy of Sciences).

- Kuz'mina, Elena Efimovna (2007). Mallory, James Patrick, ed. The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Leiden: Brill.

- Lal, B. B. (1984). Frontiers of the Indus Civilization.

- Lal, B.B. (1998). New Light on the Indus Civilization. Delhi: Aryan Books.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (2016), "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East", Nature, 536 (7617): 419–424, Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L, doi:10.1038/nature19310, PMC 5003663

, PMID 27459054

, PMID 27459054 - Lowe, John J. (2015). Participles in Rigvedic Sanskrit: The syntax and semantics of adjectival verb forms. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-100505-3.

- Mallory, J. P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth

. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1..

. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1.. - Mallory, J. P. (1998). "A European Perspective on Indo-Europeans in Asia". Dalam Mair. The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern and Central Asia. Washington DC: Institute for the Study of Man.

- Mallory, J. P. (2002). "Editor's Note". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 30: 274.

- Mallory, J.P. (2002b), "Archaeological models and Asian Indo-Europeans", dalam Sims-Williams, Nicholas, Indi-Iranian Languages and Peoples, Oxford University Press

- Mallory, J. P; Adams, D.Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press.

- Mallory, J.P. (2013), "Twenty-first century clouds over Indo-European homelands" (PDF), Journal of Language Relationship, 9: 145–154, doi:10.31826/jlr-2013-090113

- McGetchin, Douglas T. (2015), "'Orient' and 'Occident', 'East' and 'West' in the Doscourse of German Orientalists, 1790–1930", dalam Bavaj, Riccardo; Steber, Martina, Germany and 'The West': The History of a Modern Concept, Berghahn Books

- Metspalu, Mait; Gallego Romero, Irene; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Mallick, Chandana Basu; Hudjashov, Georgi; Nelis, Mari; Mägi, Reedik; Metspalu, Ene; Remm, Maido; Pitchappan, Ramasamy; Singh, Lalji; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Villems, Richard; Kivisild, Toomas (2011), "Shared and Unique Components of Human Population Structure and Genome-Wide Signals of Positive Selection in South Asia", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 89 (6): 731–744, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.010, ISSN 0002-9297, PMC 3234374

, PMID 22152676

, PMID 22152676 - Narasimhan VM, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Rohland N, Bernardos R, Mallick S, et al. (September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619

. PMID 31488661.

. PMID 31488661. - Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilisation. Oxford University Press.

- Parpola, Asko (2020). "Royal "Chariot" Burials of Sanauli near Delhi and Archaeological Correlates of Prehistoric Indo-Iranian Languages". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 8: 175–198. doi:10.23993/store.98032

.

. - Pereltsvaig, Asya; Lewis, Martin W. (2015), The Indo-European Controversy, Cambridge University Press

- Pinkney, Andrea Marion (2014), "Revealing the Vedas in 'Hinduism': Foundations and issues of interpretation of religions in South Asian Hindu traditions", dalam Turner, Bryan S.; Salemink, Oscar, Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-63646-5

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2.

- Ravinutala, Abhijith (2013). Politicizing the Past: Depictions of Indo-Aryans in Indian Textbooks from 1998–2007.

- Reddy, Krishna (2006), Indian History, Tata McGraw-Hill Education

- Rao, S. R. (1993). The Aryans in Indus Civilization.

- Reich, David (2018), Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Rocher, Ludo (1986), The Purāṇas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag

- Salmons, Joseph (2015), "Language shift and the Indo-Europanization of Europe", dalam Mailhammer, Robert; Vennemann, Theo; Olsen, Birgit Anette, Origin and Development of European Languages, Museum Tusculanum Press

- Schlegel, Friedrich von (1808). Ueber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier.

- Senthil Kumar, A.S. (2012), Read Indussian, Amarabharathi Publications & Booksellers

- Shaffer, Jim (2013) [1st Pub. 1984]. "The Indo-Aryan Invasions: Cultural Myth and Archaeological Reality". Dalam Lukacs, J. R. In The Peoples of South Asia. New York: Plenum Press. hlm. 74–90.

- Shaffer, J.; Lichtenstein, D. (1999). "Migration, Philology and South Asian Archaeology". Dalam Bronkhorst, J.; Deshpande, M. In Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia: Evidence, Interpretation and Ideology. Harvard University Press.

- Shinde, Vasant; Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; et al. (2019), "An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers", Cell, 179 (3): 729–735.e10, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.048, PMC 6800651

, PMID 31495572

, PMID 31495572 - Silva, Marina (2017), "A genetic chronology for the Indian Subcontinent points to heavily sex-biased dispersals", BMC Evolutionary Biology, 17 (1): 88, doi:10.1186/s12862-017-0936-9, PMC 5364613

, PMID 28335724

, PMID 28335724 - Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century (dalam bahasa Inggris). Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9. Diakses tanggal 7 March 2021.

- Singh, Upinder (2009), History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Longman, ISBN 978-8131716779

- Talageri, Shrikant G. (2000). The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-010-0. Diarsipkan dari versi asli tanggal 2007-09-30. Diakses tanggal 1 May 2007.

- Thapar, Romila (1996). "The Theory of Aryan Race and India: History and Politics". Social Scientist. 24 (1/3): 3–29. doi:10.2307/3520116. JSTOR 3520116.

- Thapar, Romila (2006). India: Historical Beginnings and the Concept of the Aryan. National Book Trust. ISBN 9788123747798.

- Thomason, Sarah Grey; Kaufman, Terrence (1988). Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07893-4.

- Trautmann, Thomas (2005). The Aryan Debate. Oxford University Press.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (1997). Aryans and British India (dalam bahasa Inggris). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91792-7. Diakses tanggal 7 March 2021.

- Truschke, Audrey (15 December 2020). "Hindutva's Dangerous Rewriting of History". South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (24/25). doi:10.4000/samaj.6636

. ISSN 1960-6060.

. ISSN 1960-6060. - Turner, Bryan S. (2020), "Sanskritization", International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences

- Underhill, Peter A.; et al. (2010). "Separating the post-Glacial coancestry of European and Asian y chromosomes within haplogroup R1a". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (4): 479–484. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.194. PMC 2987245

. PMID 19888303.

. PMID 19888303. - Valdiya, K. S. (2013). "The River Saraswati was a Himalayan-born River" (PDF). Current Science. 104 (1): 42.

- Varma, V. P. (1990). The Political Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- Walsh, Judith E. (2011). A Brief History of India

. Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-8143-1.

. Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-8143-1. - Warder, A. K. (2000). Indian Buddhism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (1984). "Sur le chemin du ciel" (PDF).

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (1995), "Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru state" (PDF), Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, 1 (4): 1–26, diarsipkan dari versi asli (PDF) tanggal 11 June 2007

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (1999). "Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Ṛgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic)" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 5 (1). Diarsipkan dari versi asli (PDF) tanggal 2012-02-06. .

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (17 February 2000). Kenoyer, J., ed. "The Languages of Harappa" (PDF). Proceedings of the Conference on the Indus Civilization. Madison..

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (2001). "Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 7 (3): 1–115.

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (2003). "Ein Fremdling im Rgveda". Journal of Indo-European Studies (dalam bahasa Jerman). 31 (1–2): 107–185..

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (2005). "Indocentrism". Dalam Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L. The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Routledge.

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (2006). "Rama's realm: Indocentric rewritings of early South Asian History". Dalam Fagan, Garrett. Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30592-6.

- Witzel, Michael (2006b). "Early Loan Words in Western Central Asia: Indicators of Substrate Populations, Migrations, and Trade Relations". Dalam Mair, Victor H. Contact And Exchange in the Ancient World. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2884-4.

- Witzel, Michael E. J. (2012). The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Oxford University Press.

- Witzel, Michael (2019), "Early ' Aryans' and their neighbors outside and inside India", Journal of Biosciences, 44 (3), doi:10.1007/s12038-019-9881-7

- Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei; Mittnik, Alissa; Bánffy, Eszter; Economou, Christos; Francken, Michael; Friederich, Susanne; Pena, Rafael Garrido; Hallgren, Fredrik; Khartanovich, Valery; Khokhlov, Aleksandr; Kunst, Michael; Kuznetsov, Pavel; Meller, Harald; Mochalov, Oleg; Moiseyev, Vayacheslav; Nicklisch, Nicole; Pichler, Sandra L.; Risch, Roberto; Rojo Guerra, Manuel A.; Roth, Christina; Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna; Wahl, Joachim; Meyer, Matthias; Krause, Johannes; Brown, Dorcas; Anthony, David; Cooper, Alan; Alt, Kurt Werner; Reich, David (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783

. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219

. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219  . PMID 25731166.

. PMID 25731166. - Olalde, Iñigo; et al. (2018). "The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe". Nature. 555 (7695): 190–196. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..190O. doi:10.1038/nature25738. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5973796

. PMID 29466337.

. PMID 29466337. - Saag, Lehti; Varul, Liivi; Scheib, Christiana Lyn; Stenderup, Jesper; Allentoft, Morten E.; Saag, Lauri; Pagani, Luca; Reidla, Maere; Tambets, Kristiina; Metspalu, Ene; Kriiska, Aivar; Willerslev, Eske; Kivisild, Toomas; Metspalu, Mait (2017). "Extensive Farming in Estonia Started through a Sex-Biased Migration from the Steppe". Current Biology. 27 (14): 2185–2193.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.022

. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 28712569.

. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 28712569.

- Web-sources

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2017), "Another Great Story"", review of Asko Parpola's The Roots of Hinduism; in: Inference, International Review of Science, Volume 3, Issue 2

- ^ a b Girish Shahane (September 14, 2019), Why Hindutva supporters love to hate the discredited Aryan Invasion Theory, Scroll.in

- ^ a b c Koenraad Elst, 2.3. THE PRECESSION OF THE EQUINOX

- ^ Indic Studies Foundation, Dating the Kurukshetra War

- ^ Kazanas, Nicholas. "The Collapse of the AIT and the prevalence of Indigenism: archaeological, genetic, linguistic and literary evidences" (PDF). www.omilosmeleton.gr. Diakses tanggal 23 January 2015.

- ^ a b Mukul, Akshaya (9 September 2006). "US text row resolved by Indian". The Times of India. Diarsipkan dari versi asli tanggal 7 September 2011.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (17 May 2019). "Opinion | They Peddle Myths and Call It History (Published 2019)". The New York Times. Diakses tanggal 7 March 2021.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Daniyal2018" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Pattanaik2020" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Subramanian2018_Royal" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

<ref> dengan nama "VF-Intro" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.Further reading

- Overview

Edwin Bryant, a cultural historian, has given an overview of the various "Indigenist" positions in his PhD-thesis and two subsequent publications:

- Bryant, Edwin (1997). The indigenous Aryan debate (Tesis). Columbia University.

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513777-9.

- Bryant, Edwin F.; Patton, Laurie L. (2005). The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Routledge.

The Indigenous Aryan Debate and The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture are reports of his fieldwork, primarily interviews with Indian researchers, on the reception of the Indo-Aryan migration theory in India. The Indo-Aryan Controversy is a bundle of papers by various "indigenists", including Koenraad Elst, but also a paper by Michael Witzel.

Another overview has been given by Thomas Trautmann:

- Trautmann, Thomas (2005). The Aryan Debate. Oxford University Press.

- Trautmann, Thomas (2006). Aryans and British India. Yoda Press. ISBN 9788190227216.

- Literature by "indigenous Aryans" proponents

- Elst, Koenraad (1999). Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-86471-77-4. Diarsipkan dari versi asli tanggal 2013-08-07. Diakses tanggal 2006-12-21.

- Kazanas, Nicholas (2002). "Indigenous Indo-Aryans and the Rigveda". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 30: 275–334.

- Georg Feuerstein, Subhash Kak, David Frawley, In Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India Quest Books (IL) (October, 1995) ISBN 0-8356-0720-8

- Lal, B. B. (2002), The Sarasvati flows on: The continuity of Indian culture, Aryan Books International, ISBN 81-7305-202-6.

- Lal, B. B. (2015), The Rigvedic People: Invaders? Immigrants? or Indigenous?. See also Koenraad Elst, "Book Review: The Rig Vedic People Were Indigenous to India, Not Invaders"

- Mukhyananda (1997). Vedanta: In the Context of Modern Science – A Comparative Study. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. ASIN: B0000CPAAF.

- N. S. Rajaram, The Politics of History: Aryan Invasion Theory and the Subversion of Scholarship (New Delhi: Voice of India, 1995) ISBN 81-85990-28-X.

- Talageri, S. G., The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis, New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2000 ISBN 81-7742-010-0 [1]

- Danino, Michel (April–June 2009). "A Brief Note on the Aryan Invasion Theory" (PDF). Pragati Quarterly Research Journal. Diarsipkan dari versi asli (PDF) tanggal 2015-02-03. Diakses tanggal 2015-02-03.

- Motwani, Jagat (2011). None but India (Bharat): The Cradle of Aryans, Sanskrit, Vedas, & Swastika – 'Aryan Invasion of India' and 'IE Family of Languages' Re-examined and Rebutted. iUniverse.

- Bharat

- Frawley, David (1993). Gods, Sages and Kings: Vedic Secrets of Ancient Civilization. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Criticism

- Shereen Ratnagar (2008), The Aryan homeland debate in India, in Philip L. Kohl, Mara Kozelsky, Nachman Ben-Yehuda "Selective remembrances: archaeology in the construction, commemoration, and consecration of national pasts", pp 349–378

- Suraj Bhan (2002), "Aryanization of the Indus Civilization" in Panikkar, KN, Byres, TJ and Patnaik, U (Eds), The Making of History, pp 41–55.

- Thapar, Romila (2019), "They Peddle Myths and Call It History", New York Times

- Other

- Guichard, Sylvie (2010). The Construction of History and Nationalism in India: Textbooks, Controversies and Politics. Routledge. -->

Pranala luar

- Thapar, Romila, The Aryan question revisited (1999)

- Witzel, Michael, The Home of the Aryans

- Witzel, Horseplay at Harappa, Universitas Harvard

- A tale of two horses – Frontline, edisi 11–24 November 2000.

- Linda Hess, The Indigenous Aryan Discussion on RISA-L: The Complete Text (to 10/28/96)

- Thomas Trautmann (2005), The Aryan Debate: Introduction